About 15 years after having a heart attack, an active 76-year-old man began to experience extreme weakness and fatigue. He had undergone an open-heart procedure to insert a replacement aortic valve following his heart attack. However, calcium deposits had caused deterioration in the replacement valve leading to severe valve leakage. His cardiologists in the Western U.S. recommended a second open-chest procedure.

Uncomfortable with that approach, the patient researched valve repair options. An active bicyclist in good physical condition, he wanted to avoid the arduous and painful recovery from surgery. He learned about the pioneering catheter-based transaortic valve replacement (TAVR) program at Duke and scheduled an assessment.

Question: Was an older patient who had undergone a previous open surgery a good candidate for non-surgical TAVR?

Answer: When the patient presented in April 2016, J. Kevin Harrison, MD, a structural heart specialist and medical director of the Structural Heart Disease Program at Duke, led a team that assessed the patient’s condition. His age and previous myocardial infarction, as well as the condition of the replacement valve, were key factors. The Duke team offered the patient both non-surgical TAVR and surgery. But the patient had a strong desire to avoid the recovery associated with an open-heart procedure.

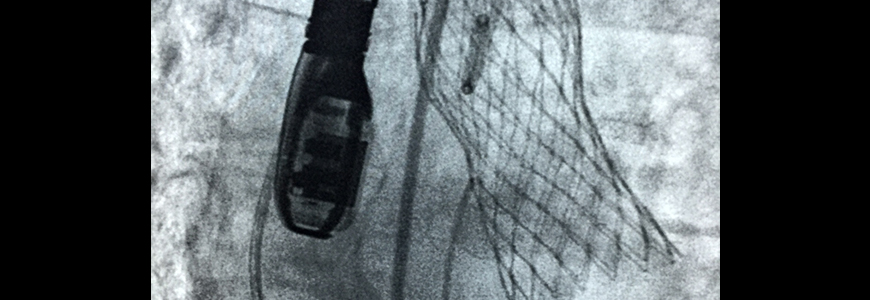

The patient also had a significant advantage favoring TAVR: the replacement valve inserted following the heart attack had a 27-mm diameter, which was large enough to accommodate a second valve. The patient underwent a successful TAVR procedure. He recovered fully and resumed an active lifestyle.

Valve diameter is a major factor in assessing replacement strategies, Harrison says. “Because of the size of the original valve, we were able to work with a large opening—in this instance, a 27-mm valve—and get a nice clean, large opening and make the repair with a catheter-based approach.” Smaller valve sizes are not uncommon. “If it is a small prosthesis, 21 mm or less, we don’t have a lot of working room without adding the risk of introducing an obstruction.”

The Duke team used the same technique employed for patients with native valve stenosis: They preserved the native leaflets, pushing them to the periphery, then inserted a stent to anchor the replacement valve, which was sewn inside the stent.

“This patient was a good example of a savvy individual who researched treatment options carefully and understood the possibilities,” Harrison says. “His preparation and personal assessment were impressive.”

Duke continues to be one of the national leaders in TAVR trials and treatment. Use of TAVR at Duke began in 2011 as a trial for high-risk patients ineligible for surgical aortic valve replacement.