In 2025, Duke Health became the first institution in the world to perform a living mitral valve replacement as well as on-table heart reanimation for transplant. The pioneering procedures not only save lives but improve organ stewardship for the field.

Living mitral valve replacement

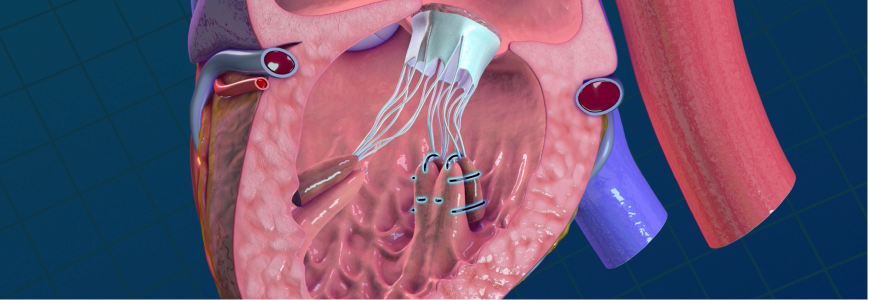

After an adolescent girl presented with sudden heart failure, she received a heart transplant. In a domino procedure, the healthy valves from her explanted heart were used to save two recipients.

A 14-year-old girl, whose own mitral valve leaflets had irreparably deteriorated due to bacterial endocarditis, received the explanted mitral valve. A 9-year-old girl with aortic stenosis from Turner syndrome also received the donor’s pulmonary valve in a living Ross procedure.

Pediatric heart surgeon Douglas Overbey, MD, MPH, was on the team performing the operations. “Three people benefited from one organ that was offered,” says Overbey. “It’s been several months now, and all three are doing well. The adolescent recipient is even back to competitive running.”

Valves that grow with a child

The cryopreserved or mechanical valves previously used for children cannot grow with them. “Other treatment options all require multiple surgeries, and we know they’re going to fail down the road,” says Overbey. Originally innovated at Duke, partial heart transplants give children tissues that can grow with them.

Duke has performed over 25 partial heart transplants to date including domino and living Ross procedures. Partial heart recipients receive immunosuppression at a dosage that is considered non-life-altering, and recipients have continued to grow and thrive since the first partial heart procedure three years ago. The living mitral valve replacement is another way Duke continues to improve organ stewardship and pediatric heart surgery.

On-table heart reanimation

Donation after circulatory death (DCD) requires a heart to be evaluated before donation, but current perfusion technologies cannot be used for small pediatric donor hearts.

To overcome this, a Duke team developed a novel technique that temporarily reanimates the donor heart outside of the body on a surgical table using extracorporeal membrane oxygenation — allowing surgeons to assess the organ’s viability before transplant. Duke scientists call the new technique on-table heart reanimation. The first-of-its-kind case saved the life of a then-3-month-old patient, who received a reanimated donor heart earlier this year.

Both techniques have the potential to save as many young lives as there are viable pediatric donor hearts currently going unused. “We offer a lot of innovation. We have access to organ offers that other centers in the nation generally wouldn’t access, resulting in a lower waitlist time at Duke,” says Overbey, who co-authored the paper on the reanimation technique in the New England Journal of Medicine along with Duke physicians Joseph W. Turek, MD, PhD, MBA, chief of pediatric cardiac surgery, and John A. Kucera, MD.

“Our novel solutions to pediatric heart problems, whether aiming to increase the donor pool or implanting living valves that grow with children, are all born out of necessity and a desire to improve the lives of our most vulnerable patients,” says Turek.

The Duke Pediatric Heart Program

Treating the full spectrum of pediatric heart conditions and performing more than 450 index heart operations in 2024, the program is a leader by volume and outcomes in the country. The team also performs significantly more complicated procedures than many other centers nationally and is recognized as #3 in the nation for high-risk pediatric heart surgery by U.S. News & World Report.

“We hold several multidisciplinary conferences weekly to provide optimal care,” says Overbey. “Referring providers are welcome to join and contribute. As we discharge, our cardiologists and coordinators collaborate with referring providers to create a plan for continuing care.”

Early referral can improve care. “We have a robust fetal program for patients before birth,” Overbey says. “After birth, we want to get to know those patients early, even if they’re not ready for surgery yet. This gives us time to explore other treatments and perform a full workup. Once a patient is diagnosed with congenital heart disease, it’s never too early to refer.”