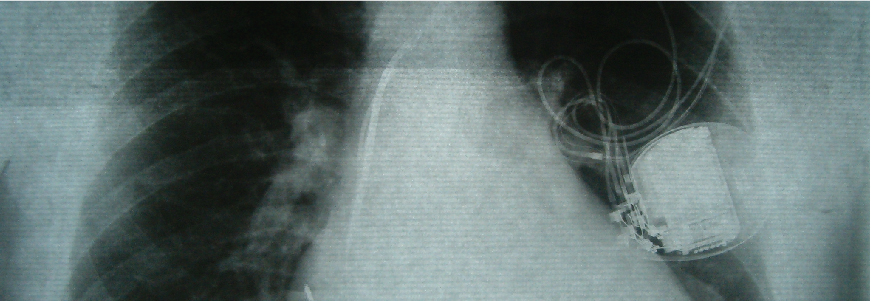

Medicare patients whose implantable heart devices became infected were less likely to die from the complication if they had the leads removed compared to patients who only received antibiotics, according to the largest study on the topic, led by the Duke Clinical Research Institute (DCRI).

The study showed that just 18% of patients with device-related infections underwent surgeries to have their pacemakers or defibrillators removed, even though removal is recommended by all leading medical society treatment guidelines. The risk of death is 43% lower if lead removal guidelines are followed, the study authors reported.

Presented in April at the 2022 American College of Cardiology Scientific Sessions, the analysis highlights the risk of cardiac device-related infection and demonstrates the significant gaps in guideline adherence.

Duke electrophysiologist and cardiologist Sean D. Pokorney, MD, MBA, and colleagues launched the study in 2021, reviewing Medicare data for nearly 1.1 million patients who received cardiac implantable electronic devices (CIEDs) between 2006 and 2019.

“This is an important message about a persistent gap in care: These devices should be removed when an infection occurs, and their removal saves lives,” says Pokorney, a DCRI member.

Clear survival benefit

Among those studied, 11,619 (about 1%) developed infections a year or more after implantation. Only 13% of the patients had the device removed within six days of infection, and an additional 5% had the device removed between days seven and 30.

The vast majority—nearly 82 %—were treated solely with antibiotics, despite numerous earlier studies showing antibiotics fail to resolve infections involving CIEDs. The earlier analyses led to a 2017 consensus of leading health organizations to recommend removal of CIEDs when a definitive infection is diagnosed.

In the current study, the researchers found that removing the devices had a clear survival benefit. The death rate for those who did not have their devices removed was 32.4% in the year after an infection was diagnosed, compared with a rate of 18.5% among patients who underwent extraction within six days and 23.2% for patients who had extractions on days seven to 30.

“Any extraction was associated with lower mortality when compared to no extraction, but the highest benefit was to those who had devices removed within six days of an infection,” Pokorney says. “This speaks to the importance of putting systems in place to identify these patients and get them quickly and appropriately treated, because delays in care result in higher mortality.”

With funding from Philips, which markets devices used in CIED extraction procedures, and leadership from Pokorney and cardiologist Christopher B. Granger, MD, the DCRI plans to launch a quality improvement demonstration project to address the gap in care for patients with CIED infection within three health care systems in the United States.

In addition to Pokorney and Granger, Duke authors include biostatisticians Lindsay Zepel, MS, and Melissa A. Greiner, MS; Eric Black-Maier, MD; and physicians Robert K. Lewis, MD; Donald D. Hegland, MD; and Jonathan P. Piccini, MD.