The timing of sudden cardiac death (SCD) in patients with end stage renal disease (ESRD) undergoing hemodialysis (HD) has prompted concern among nephrologists about existing dialytic therapy, particularly for patients undergoing the commonly prescribed thrice-weekly schedule.

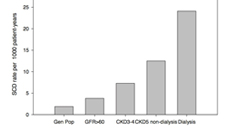

In the United States, 466,000 patients require weekly HD, and the number continues to rise. Nephrologists acknowledge a cardiovascular mortality rate of approximately 25 percent among patients with ESRD undergoing HD. In the United States, more HD recipients die from SCD than any other factor.

Patrick H. Pun, MD, MHS, a Duke nephrologist, says dialysis clinicians know that most sudden deaths occur just before or immediately after dialysis on the first treatment day of the week among patients who are prescribed HD on a Monday-Wednesday-Friday or a Tuesday-Thursday-Saturday schedule.

“We need to do a better job of understanding risk factors that are associated with this challenge in hemodialysis patients so we can begin to design and incorporate prevention strategies,” Pun says. “Given the pattern of deaths in the HD cycle, we must learn more about relationships between the timing of the deaths, the mechanism of death, and the hemodialysis prescription.”

Accumulation of potassium and fluid during the dialysis-free weekend and the rapid correction of these problems with dialysis on the first HD treatment of the week may act as triggers for cardiac arrest, Pun says. But more data are needed to help dialysis clinicians know how to adjust HD prescriptions safely, and whether or not such adjustments will reduce the risk of cardiac arrest.

Pun and several Duke nephrology colleagues highlighted the HD mortality factors in papers published in nephrology journals in 2017. The risks associated with concentrations of serum and dialytic potassium among patients undergoing HD were reviewed in the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. A related paper in the American Journal of Kidney Disease summarized the epidemiology, pathophysiology, and risk factors for SCD among HD recipients.

Pun and several Duke nephrology colleagues highlighted the HD mortality factors in papers published in nephrology journals in 2017. The risks associated with concentrations of serum and dialytic potassium among patients undergoing HD were reviewed in the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. A related paper in the American Journal of Kidney Disease summarized the epidemiology, pathophysiology, and risk factors for SCD among HD recipients.

Pun says nephrologists must rethink the management of sudden death prevention in patients receiving HD. “Dialysis patients do not respond as well as non-dialysis patients to conventional treatments to prevent sudden death,” Pun says. “And the dialysis procedure itself introduces risk, even though patients cannot survive without it. We need to understand more about what causes sudden death in our patients before we can design effective treatments.”

A co-author of both papers, Pun will serve as the co-principal investigator for the RADAR study, a pilot clinical trial beginning later this year that will examine the effect of modifying the dialysis prescription in response to monitoring of blood electrolyte levels on the risk of heart arrhythmias.

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, a division of NIH, provided funding. Duke Health and Harvard Medical School will collaborate on the trial, which is expected to enroll about 40 patients.