A national prospective study analyzing variations in the apolipoprotein L1 (APOL1) gene may provide a key to improving availability to and outcomes after kidney transplant in African American patients by providing data to help transplant specialists predict donor risk, assess the potential performance of a donated organ and potentially increase the number of living donor transplants performed for African American recipients.

The risk of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) is higher among African Americans than in other racial groups—a factor that has been a key factor in the transplant decision-making process for decades within the kidney transplant community, says Matthew J. Ellis, MD, medical director of the Duke Adult Kidney Transplant program.

African Americans, who make up 12% of the U.S. population, are overrepresented on kidney transplant waiting lists nationally and at Duke, a high-volume transplant center. African Americans comprise approximately 60% of the waiting list at Duke and about 30% nationwide. Living and deceased donors are less common within this ethnic group; additionally, African Americans recipients are biologically disadvantaged because of blood typing and compatibility issues factors which reduce the number of organ offers an African-American recipient receives.

Ellis and Rasheed A. Gbadegesin, MD, MBBS, a geneticist and pediatric nephrologist, are the Duke representatives in the APOL1 Long-term Kidney Transplantation Outcomes Network (APOLLO) study. Gbadegesin is one of three principal regional investigators; Ellis is a sub-investigator.

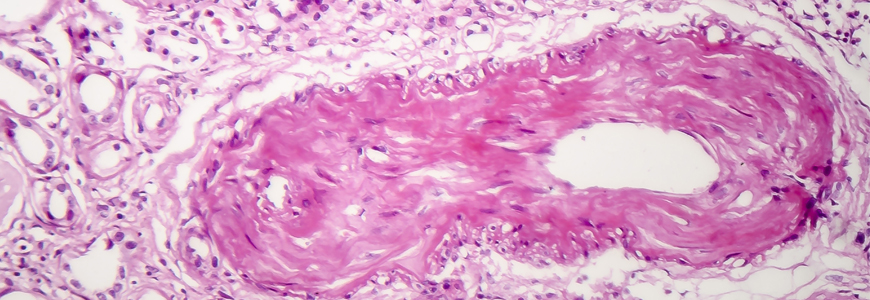

The national study will genotype every deceased African American donor to help researchers understand the impact of the APOL1 variants on outcomes of kidneys donated by African Americans with two or more of the gene variants. “The hypothesis is that if an African American donor has two or more of the gene variants, the outcome of the donation will be worse than if the donor has one or fewer variants,” Ellis says.

Genetic research raises new questions, opportunities in transplant

“When you look at all populations, everything being equal, kidney disease is more likely to be present in an individual with African American ancestry,” Ellis says. “From a medical perspective, kidney transplants in which the donor is African American generally don’t last as long as donations from other ethnic groups.”

Approximately 15 years ago, kidney researchers recognized that the presence of variations of the APOL1 gene in African Americans indicated that those individuals were more likely to experience ESRD. The findings, based on retrospective research, prompted national transplant leaders to question existing knowledge regarding kidney longevity and ethnicity.

“Now we have to push through APOLLO to take the research further,” Ellis says. “If the risk is indeed related to genetic variation, we need to prove that in a prospective manner. If we can do it, the finding has the potential change everything about the kidney allocation system.”

If the findings suggest that the presence of the APOL1 gene is the key marker in predicting long-term kidney function from an African American donor, the study would serve as an indication that race and ethnicity may not be factors. This outcome would necessitate widespread genetic testing at the time of living or deceased donation, which could increase both deceased donor organ utilization and living donations.

If the results provide the definitive link to the APOL1 gene, transplant specialists would likely initiate plans to make the test more broadly available. The incorporation of a genetic test would require the creation of a new model for the matching process, incorporating the results of the test and eliminating African American ethnicity as part of the estimating equation at the heart of the kidney allocation system.

“It would be a critical finding,” Ellis says. “But there’s still a lot of work ahead in making the test available and determining how to incorporate the test results into the allocation system.”