The Duke Adult Kidney Transplant Program is participating in the Collaborative Innovation and Improvement Network (COIIN) project, a national Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) pilot program designed to close the gap between the numbers of patients waiting for organs and those who receive transplants by encouraging the use of organs with higher risk scores.

At the end of 2017, the waiting list for a kidney transplant in the United States stood at 95,063, according to United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS); 19,849 transplants were performed that year. Patients wait an average of three to five years for transplant at most centers.

Matthew J. Ellis, MD, medical director of the Adult Kidney Transplant Program, says the objective of the pilot is to encourage the use of kidneys recovered from deceased donors that historically were discarded because of safety metrics assigning risk as well as concerns about unfavorable outcomes.

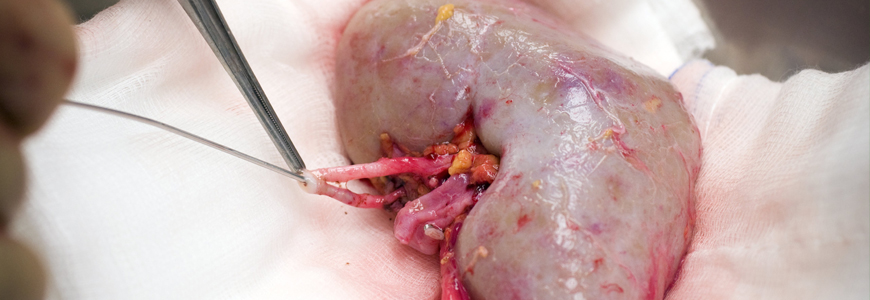

“Some organs recovered from deceased donors are not used for implantation currently for a variety of safety reasons,” Ellis says. “Donor quality or damage to the organ during procurement are often factors.” But many discarded organs are safe and appropriate, he says, particularly for older patients with comorbidities who are on the waiting list.

The COIIN project encourages transplant centers to review their processes collaboratively to identify situations in which previously discarded organs can be used safely. Duke was among 36 U.S. hospitals selected in October 2017 during a competitive process for the second phase of COIIN.

All organs for transplant in the United States are assigned a Kidney Donor Profile Index (KDPI) to help determine how long the kidney is likely to function compared with other kidneys. Low scores are preferred: a KDPI score of 30 percent means the kidney is likely to function longer than 70 percent of available kidneys.

“The goal is to direct transplant professionals to identify more patients in whom we can safely use kidneys with higher KDPI scores,” Ellis says. “COIIN will help centers become more comfortable with the concept of using these organs without the risk of being penalized if outcomes are not as good as a lower KPDI organ.”

Melissa D. Williams, RN, who coordinates Quality Assurance and Performance Improvement for Duke Transplant Center, says the COIIN project is likely to produce incremental increases in deceased donor use as the program begins. “The organs that are not being utilized now may offer survival benefits,” Williams says. “This is particularly true for older patients with diabetes, for example, who may be on dialysis.”

Hospitals must have performed more than 45 transplants during the previous year to qualify for COIIN participation. During 2017, Duke’s program performed 178 adult kidney transplants.