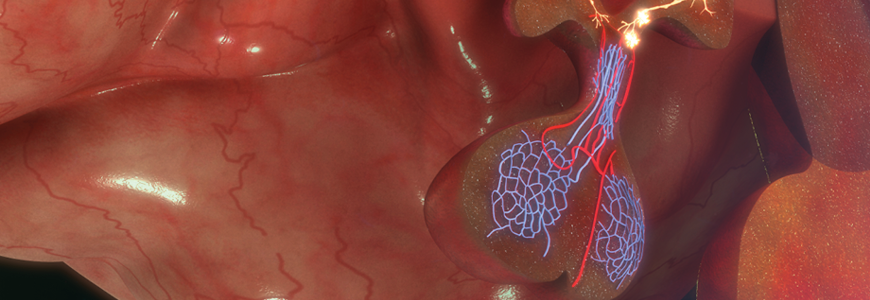

A seven-year-old male patient presented to Amanda V. Jenson, MD, pediatric neurosurgeon, after an MRI revealed a large pituitary gland mass. The boy first presented to a neuroophthalmologist after experiencing a significant decline in his vision. His MRI showed a large, homogenously enhancing lesion measuring 2.4 cm by 4.1 cm by 3.6 cm, causing expansion and remodeling of the sella turcica. The mass was also displacing the cavernous sinuses outward and the optic chiasm upwards, rendering him almost blind. The tumor was wrapped around the carotid arteries bilaterally, causing additional concern.

“This was a very unique case. Prolactinomas this large in the pediatric population are very rare,” says Jenson. “Due to the position of the tumor and aggressive nature, I brought in other members of our neurosurgery and pediatric ear, nose, and throat (ENT) teams to ensure we approached this case with care and precision,” she adds.

Question: How did Jenson assemble a team to resect the patient’s prolactinoma?

Answer: Jenson collaborated with pediatric ENT Eileen M. Raynor, MD, to approach the surgery transnasally. “Transnasal approaches with children are challenging because their sinuses haven’t fully pneumatized yet, and their noses are just much smaller. This case had additional complexity because of a false membrane through the tumor, essentially making it two distinct masses, both of which were splaying the optic nerve,” says Jenson.

Raynor prepared the surgical approach and Jenson resected the tumor. Jenson removed a large portion of the tumor, but an MRI performed postoperatively showed half of the tumor remained, which was being kept up by a membrane. “We realized a second procedure was necessary to get the remaining tumor out by having to pierce that membrane. At the time of the first surgery, it looked like the edge of the tumor, which would mean the optic nerves and optic chiasm were right above it. That’s why we stopped initially to be safe and preserve his vision,” said Jenson.

The second procedure was performed in an intraoperative MRI suite, so Jenson and Raynor could scan him while still sterile and asleep to make sure all of the tumor came out, so they could go back in if needed. Because aggressive prolactinomas are rare, Jenson consulted with adult pituitary neurosurgeon Jordan M. Komisarow, MD, on the surgical approach of the tumor invading the cavernous sinuses bilaterally.

Jenson successfully resected most of the tumor, but parts wrapped around the carotid arteries, invading the cavernous sinus, could not be removed safely without significant risk to the patient. With Komisarow’s advice, some of the tumor was intentionally left behind because cabergoline could be used after surgery to help shrink the remaining tumor without imposing additional risk to the patient.

Jenson performed an abdominal fat graft to pack the open cavity after the tumor was removed, and Raynor performed a nasoseptal mucosal flap to hold this graft in while it healed. “This prevents [cerebrospinal fluid] CSF from leaking into the space until scar tissue forms,” explains Jenson. “This is a procedure that few medical centers can perform, as it requires a team of specialists and highly skilled surgeons in pediatric skull-based ENTs, pediatric neurosurgery with additional skull-based training, and also pediatric neuro-ophthalmologists, pediatric endocrinologists, and pediatric neurooncologists” she adds.

“To shrink the remaining tumor, we had to suppress prolactin secretion with the dopamine receptor agonist, cabergoline,” explains Jenson. Follow-up imaging several months after the surgery shows cabergoline was working. “The remaining tumor shrank, and continues to shrink, leading to less compression of his carotid arteries. His vision was thankfully restored after the first operation.”

Because of the diagnosis, Jenson also referred the patient to cancer genetics to determine if the patient had a predisposition syndrome. “Thankfully, the patient was negative for a tumor predisposition syndrome,” says Jenson.

Pediatric endocrinologist Elizabeth Green, MD, was also involved in the patient’s case and continued outpatient treatment to ensure hormone function remains optimal.

Jenson concludes, “This case was not straightforward, but at Duke, we have experts in every subspecialty required to achieve a great result for this patient. We are one of the unique medical centers that can take on these rare and complex cases, and provide good outcomes for patients.”

To refer a patient to Duke Pediatric Neurosurgery, call 919-684-5013.