Lindsay Y. King, MD, MPH, Duke’s new medical director of the Liver Transplant Program, has been quietly preparing to lead the program for several years.

Recruited to Duke in 2015 by Carl L. Berg, MD, former medical director, King had known Berg as her medical school professor-turned-professional-mentor. In October 2022, King was promoted to the medical director role when Berg shifted his focus to a significant NIH immunosuppression research initiative. King discusses the program’s objectives under her leadership in the following interview.

What are your goals for the future of the liver transplant program at Duke?

The most effective actions we can take are those that address the gap between patients in need and available organs. Our priority is to sustain a high transplant rate and convert organ offers into successful transplants. Our team knows that when we receive an organ offer, as surgeons and hepatologists, we try to make that work for one of our patients in need. Addressing the imbalance between supply and demand will require growth, and we see several key steps to achieve that growth even in a program that is one of the most successful in the nation.

Fortunately, with the leadership of clinicians such as Debra L. Sudan, MD, chief of the Division of Abdominal Transplant Surgery and director of the Pediatric Liver Transplant Program, and many other medical and surgical specialists, we are in a good position to address that imbalance.

We want to expand our living donor program, continue to utilize organs contributed through the donation-after-circulatory-death (DCD) protocol, and increase access to organs with the use of normothermic machine perfusion (NMP) that reduces injury to the liver from preservation prior to transplantation. We will also strengthen relationships within our own specialty teams to continue to deepen our multidisciplinary approach to transplantation. And it’s obviously important that we expand our relationships with referring providers, including both gastroenterologists and primary care physicians.

What is the biggest challenge in liver transplantation now?

The top priority is getting our patients who need an organ into transplant as soon as possible. Emphasizing the need to help our patients receive transplants is the key to everything we do. I’m honored to have stepped into role following the successful tenure of Dr. Berg, who set the stage for this priority. We are building a strong team for continuing growth.

Our living donor program will be another key to growth. Matthew R. Kappus, MD, director of the living donor program, is improving patient education and outreach. Lisa McElroy, MD, MS, a surgeon, leads research studying access to transplant for underserved populations.

We also want to increase transplantation of Hepatitis C positive and Hepatitis B positive organs, which have become important drivers of growth. With the DCD program and the use of NMP for organ transport, we are on the verge of taking significant steps toward increasing volume while maintaining our excellent outcomes.

You have cited the importance of strengthening relationships with referring physicians. How will you begin that effort?

It’s important that we continue to expand access to transplant because there are many people in NC and beyond with end-stage liver disease we want to identify, connect with, and offer help. To do this, we need excellent working relationships with referring gastroenterologists and primary care practices to help us identify those patients. We want these to be partner relationships.

We offer a streamlined referral process that makes it easy for referring physicians to communicate regularly with our team. We want to make it easy for referring providers to work with us, and we want to establish a strong working relationship.

In the future, we hope to offer locations beyond Durham to expand the program’s physical footprint. This is part of our long-term growth plan. Telehealth certainly helps, and we use it effectively. But we must find ways to provide better care for people who live long distances away to help them avoid long round trips.

How critical is the program’s ongoing research?

Research will always be at the core of our transplant program. Dr. Berg’s work on biomarkers is one big part of that, but we have several researchers pursuing pathways that will improve outcomes and transplant access. (Berg now serves as medical director of abdominal transplant). We were pleased to recruit Kara Wegermann, PhD, a medical instructor and researcher who will focus on hepatocellular carcinoma when she joins our team in the summer.

One of things I have learned is that a high-performing transplant program literally takes a village to achieve great outcomes, continue sustained volume growth, and generate new research. I’m fortunate to have an amazing team of nurses, hepatologists, surgeons, coordinators, social workers, administrators and many, many other contributors who lead growth in our liver transplant program, research initiatives, patient education, and outreach.

For more information or to refer a patient, view our Duke Liver Transplant referral form or call 800-249-5864.

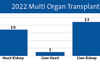

Duke is a leader in outcomes

Duke’s liver transplant program is among the national leaders in volume as well as long-term survival rate. The program also exceeds the national average in wait time for transplant with median wait time of 85 days at Duke compared to an average of 240 days nationally, according to the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients.

Duke is also among the leaders in one-year survival rates post-transplant, but King says the program wants their patients to lead long, active lives after a liver transplant. Metrics for Duke’s outcomes 3-year patient survival also exceed the national average.

“While Duke is a top program for one-year survival after transplant, we want our patients to live many, many years and enjoy full lives,” King says. “If they want to work, we want help them return to work. Or be a parent or a grandparent—whatever their goals are.”