Duke liver transplant specialists will analyze the value of biomarkers to monitor organ health following transplant as part of an NIH-sponsored trial designed to lower the use of antirejection drugs and preserve kidney health.

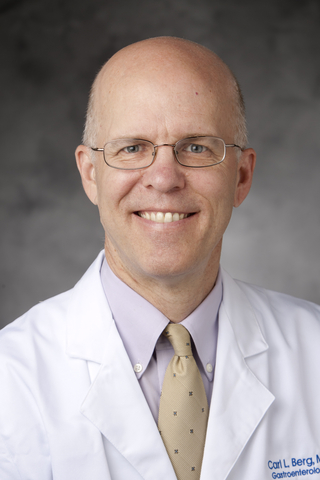

Blood tests will provide biomarkers that enable physicians to monitor a transplanted organ and customize antirejection drug dosing for each patient. If the multicenter trial yields favorable results, the pace at which antirejection drugs are tapered could be reduced by two years or more, says Carl L. Berg, MD, a transplant hepatologist and medical director of the Duke Abdominal Transplant Program.

“During the last 30 or 40 years, we typically have monitored immunosuppressed rejection by looking at lab results and making step-by-step reductions or increases in the dosing,” Berg says. “Our decisions were based on liver tests. But that strategy has lacked the precision of a personalized approach.”

Calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs), tacrolimus and cyclosporine, remain the cornerstone therapy for immunosuppression following liver transplant. But CNI use causes chronic kidney disease (CKD) in a significant percentage of liver transplant recipients. And in some cases, CNIs increase the risk for end-stage renal disease.

Researchers hypothesize that the biomarkers (TruGraf Liver, Eurofin Scientific, Luxembourg) will allow specialists to rapidly taper immunosuppression without causing rejection while enhancing long-term kidney health, Berg says. Researchers at the Feinberg School of Medicine at Northwestern University developed the biomarkers that provide snapshots of the immune system’s response to a new organ and guide immunosuppression.

“If the organ is quiet and everything is proceeding well, we can taper the immunosuppression more rapidly,” Berg says. “These blood tests can help guide our tapering regimen with the goal of getting down to lower levels of immunosuppression within less than a year compared to a typical timeframe of three to five years.”

400 patients involved in multicenter trial

Duke is one of seven institutions participating in the seven-year, randomized trial supported by The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). Northwestern is the lead center, and other consortium members include Mt. Sinai, University of Pennsylvania, two sites in the Baylor University system, and the University of Washington. The trial will assess biomarkers in 400 patients; 60 to 80 of which will have undergone transplantation at Duke.

The research consortium is part of the NIAID’s Clinical Trials in Organ Transplantation (CTOT) initiative. The analysis of liver biomarkers is one of four significant grants awarded to Duke last year. Other projects include antirejection research in lung as well as adult and pediatric kidneys. Berg will be the principal investigator at the Duke site for the liver immunosuppression trial.

“This grant is an indication at the national level that Duke transplant has become an effective, high-volume contributor to liver research as a leading center in terms of volume and excellent outcomes,” Berg says. “There are not many institutions that secure four major competitive CTOT transplant grants.”

Duke’s liver transplant volume was a significant factor, Berg says, because of the trial’s need for centers with high patient numbers to help test the biomarker hypothesis. As one of the larger volume liver transplant centers in the U.S., the Duke Transplant Center has the infrastructure to support a large trial and a track record of clinical excellence and innovation in abdominal transplant, Berg adds.

An experienced transplant specialist, Berg is also a former president of the United Network for Organ Sharing, the private, non-profit organization that manages U.S. organ transplantation. He participated previously in a large-scale research consortium analyzing adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation at the University of Virginia before joining Duke.