A male patient with Alport syndrome experienced progressive kidney function decline culminating in dialysis at age 34. As a result of structural dysfunction and resultant leakage caused by the genetic disease, the patient explored transplant options. In 2016, at age 38, he was placed on the kidney transplant wait list after an evaluation by the Duke Kidney Transplant program.

Though clinically unrelated, the patient subsequently developed non-ischemic cardiomyopathy. A defibrillator was implanted the same year. During the patient’s second year on the waitlist, monitoring revealed a significant decline in the patient’s heart function. Cardiac pumping function dropped below acceptable kidney transplant thresholds.

As a result, the patient was removed from the kidney wait list in 2019 to allow cardiologists to monitor and treat the cardiomyopathy. Although the patient’s cardiovascular function was abnormal and declining, the patient did not yet meet the standards for a heart transplant.

“This was an unusual situation in which the patient’s heart function was no longer adequate to perfuse a new kidney transplant, but the cardiac function was not at a level that would qualify for a heart transplant,” says Matthew J. Ellis, MD, medical director of the kidney transplant program.

What options could Duke Health specialists offer the patient, who now faced two potentially life-threatening conditions?

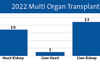

Because the patient’s cardiac function continued to decline, the heart and kidney transplant teams conducted a rigorous clinical assessment that concluded with a recommendation for simultaneous heart-kidney transplant (SHKT). The procedure was completed in December 2022. Duke Health ranks among the top 10 centers nationally by volume for double-organ procedures.

Duke transplant teams have performed 56 double-organ heart-kidney transplants. The procedures have become more frequent during the past decade; Duke has completed four during 2023, according to the Organ Procurement & Transplantation Network (OPTN).

The heart was from a donor with a prior Hepatitis B (HBV) infection. Adam D. DeVore, MD, MHS, medical director of the Duke Heart Transplant program, said the transplant was the third procedure performed by Duke using an HBc-Ab-positive heart.

“Although the patient is technically exposed at time of transplant, we work with our infectious disease teams, provide immunoglobulins, and offer preventive medicines. The patients don’t actually become infected with HBV,” DeVore says. “HBc-Ab-positive donors are increasingly utilized in solid organ transplantation,” DeVore adds.

The patient underwent extensive testing before the decision was made to list him for a simultaneous transplant, DeVore says. “There are many factors to consider and many tests to conduct,” DeVore says. “We perform exercise testing, catheterization, heart imaging, echocardiograms, as well as other analyses before pulling the results together to assess the risk of surgery and the potential for good long-term outcomes after the procedures.”

DeVore was one of 13 transplant clinicians who authored a scientific statement published in July in Circulation that emphasizes the need for clear clinical guidance regarding both SHKT and heart-liver transplantation. The statement reviews the impact of pre-transplantation renal and hepatic dysfunction on post-transplant outcomes, recommends an approach to patient selection for double-organ procedures, and explores the ethics of multiorgan transplantation.

Cohesive, multidisciplinary collaboration—by design

“This patient’s pre-transplant scenario is illustrative of the experience shared by many patients,” Ellis says. “Their journeys are often nonlinear. Many unexpected changes can occur that create new challenges. That’s why it was important for this patient to be in the Duke transplant program’s care.

“His eventual double-organ transplant was a result of the collaborative culture of our transplant teams. We work closely together across all organ groups to evaluate challenges and make decisions that offer the best outcomes for our patients.”

Duke’s ranking as a top-10 center for double-organ transplants is a result of a deliberate, collaborative culture that has enabled the growth of complex, multi-organ procedures, Ellis and DeVore says. At many national medical centers, transplant teams are located in separate clinical spaces.

“But by design, we work in close partnership at Duke,” Ellis adds. “Our patients are in the same areas; our clinical teams overlap daily. Our collaboration reflects a deliberate organizational approach.”

Duke transplant teams demonstrate both high volume and good outcomes because of the emphasis “to gently push the envelope to help more people receive more organs,” Ellis says. Both Ellis and DeVore emphasized that ongoing organ shortages for patients who need kidney and heart transplants highlight the need to increase utilization when possible. “We have therapies who can keep patients with chronic disease healthier,” DeVore says. “But the best long-term solution is often a dual-organ transplant.”

To facilitate a solid organ transplant evaluation for your patient, please refer to our transplant referral forms.