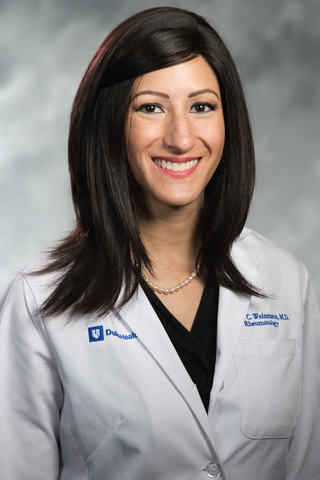

A Duke rheumatologist is focusing her efforts on immune-related adverse events (irAEs) as part of a collaboration with oncologists at the Duke Cancer Institute.

Sophia C. Weinmann, MD, works with patients referred from the Duke Cancer Institute with melanoma, lung, or other cancers being treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. She is among a growing number of clinicians beginning to explore treatments for the relatively new disease conditions recognized as irAEs.

Because of the need to maintain accelerated therapy for patients with cancer who are experiencing irAEs, the Duke Division of Rheumatology and Immunology has preserved dedicated appointment time in Weinmann’s clinic to allow for prompt evaluation, treatment and feedback to oncologists. Before Weinmann joined the faculty in 2017, patients did not have access to a clinician working regularly with irAEs to provide an expedited evaluation. Most patients can now be seen within two weeks.

“Some of the patients I see are developing patterns of disease that we recognize as rheumatic irAEs such as inflammatory arthritis or polymyalgia rheumatica after receiving immune checkpoint blockade,” Weinmann adds. The amplified immune response can also trigger autoimmunity in the gastrointestinal tract, lungs, and skin such as colitis, pneumonitis, and vitiligo—all identified as irAEs, she says. In some cases, immune checkpoint blockade must be withheld temporarily to allow patients to recover from symptoms of irAEs. Patients may be able to continue their treatments with added immunosuppressive therapies. Because of the lack of large study populations with rheumatic irAEs, Weinmann cautions that the treatment approach must be individualized. She focuses on the patient’s quality of life as the response to the cancer therapy is assessed.

All of the effects of checkpoint inhibitors are not fully understood, Weinmann says, but oncologists and rheumatologists are learning to recognize rheumatic irAEs earlier. Some rheumatic irAEs are self-limited and will resolve when the immune checkpoint blockade is stopped. But if patients need to continue their cancer therapy despite irAEs or if the patients’ symptoms do not resolve, Weinmann advises the patient and oncology team.

Weinmann works closely with April K.S. Salama, M.D., a medical oncologist specializing in advanced melanoma, to identify patients with irAEs who may benefit from a rheumatology consult. She also collaborates regularly with the Duke thoracic oncology group, including Jeffrey Crawford, MD and Neal E. Ready, MD, PhD.

Patients with underlying rheumatologic diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis or lupus may also develop cancer, which is another patient population that Dr. Weinmann follows. Many of these patients may benefit from treatment with checkpoint inhibitors for cancer.

Historically, clinical trials have excluded patients with autoimmune disease from receiving immune checkpoint blockade because of concerns that the immune system would “go rogue,” Weinmann says. “In theory, this is a valid point – these patients with rheumatoid arthritis or other rheumatologic disease have been on medications to suppress their immune system, so giving them medications that bolster the immune system to treat their cancer seems counter-intuitive.”

But Weinmann says newer findings indicate that patients with preexisting rheumatologic disease who are treated with immune checkpoint blockade have about a 30 to 40 percent risk of disease flare depending on the cohort studied. “This means that up to 70 percent of my patients will not have worsening disease,” she says. “Knowing that the available data shows that the odds are in my patients’ favor despite the mechanism of these treatments gives hope to me and my patients.”