A new drug offers hope for young boys with the progressive neuromuscular disease Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) by potentially offering an alternative to standard glucocorticoids.

Interim results from a 24-month clinical trial at Duke and other institutions suggest that the investigational drug, vamorolone, may retain or improve the effects of current steroid treatments while reducing the health risks associated with long-term steroid use.

Vamorolone is an anti-inflammatory steroid that differs from all 33 drugs in the corticosteroid class because of a distinct interaction with the body’s glucocorticoid receptors. Duke’s participation in the study is part of a larger, multi-center global trial.

Similar efficacy to standard-of-care

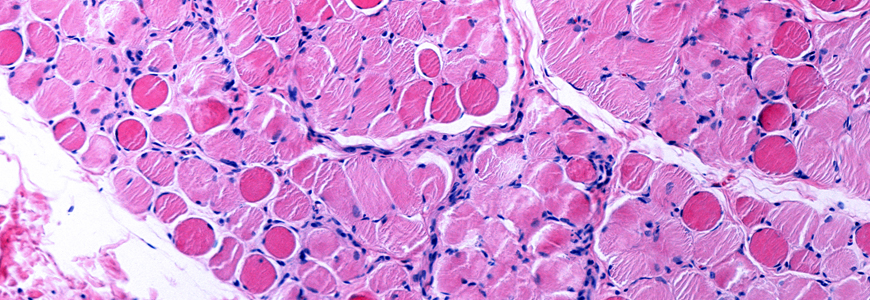

Published in September 2020 in the journal PLOS Medicine, the findings are significant because they suggest the drug may offer an alternative treatment option for young patients with DMD that reduces the side effects commonly associated with long-term, high-dose exposure to prednisone or deflazacort while possibly retaining the therapeutic benefit of this class of drugs. Steroid therapy is currently the only treatment that has been shown to slow the effects of DMD, an irreversible disease that leads to progressive muscle weakness, atrophy, and scar tissue formation in boys.

“This is potentially great news for these boys who are just beginning the steroid regimen that is our standard-of-care treatment,” says Edward C. Smith, MD, a pediatric neurologist, co-director of the Duke Children’s Neuromuscular Program, and a clinical investigator in the trial.

“One of our biggest concerns with long-term, high-dose steroid treatment in these patients is the negative impact on linear growth and bone density,” Smith says. “Thus far, based on the interim results from this trial, we may be seeing a much less negative impact on bone health among patients using vamorolone, and the height of boys taking this drug seems to be preserved.”

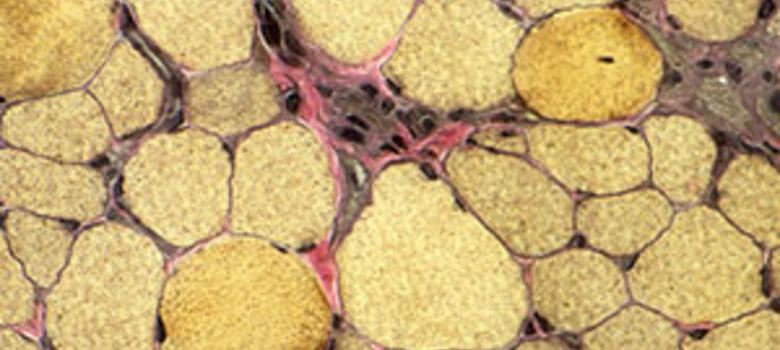

Not only does chronic steroid use lead to premature closure of bone growth plates leading to short stature, Smith says, but over time, steroids also cause osteopenia and increased fractures. Chronic steroid exposure also frequently causes significant weight gain, cataracts, and delayed puberty. Despite the side effects, steroid therapy—in addition to improvements to cardiac, pulmonary, orthopaedic, nutritional therapies—has been shown to extend patients’ mobility and life span. Patients now frequently live into their 30s, but ultimately succumb to cardiac or respiratory failure.

“Having a potential steroid alternative that is better-tolerated than current options could also have a broader application to other conditions beyond DMD,” Smith adds.

DMD signs and symptoms

A severe type of muscular dystrophy, DMD is caused by a genetic inability to create dystrophin, a protein that protects skeletal and heart muscle from injury caused by normal muscle contraction. Because the DMD gene is on the X chromosome, the disease primarily affects boys. There is no cure.

Smith says patients are typically diagnosed between ages 4 and 6 after exhibiting delayed motor development. Neurocognitive and behavioral function are often abnormal as well. Hypertrophy of the calf muscles may also be observed, and the creatine kinase level is high, indicative of muscle injury.

“The boys tend to do relatively well until about six years of age,” he says. “Then weakness becomes more pronounced and eventually impacts their ability to stand and walk.”

Findings and future study

Following completion of the six-month study, the 46 trial participants were given the option to transition to standard-of-care using prednisone or deflazacort or continue treatment with vamorolone through enrollment in a two-year, long-term extension study. All participants opted to continue treatment with vamorolone.

“We saw statistically significant improvements in the outcome measures in this part of the overall trial in boys treated with the two highest doses of vamorolone for 18 months, with improvements in strength and function,” Smith says. “These improvements appear to be similar to what is seen in steroid-treated boys, based on data from DMD natural history studies. Additionally, vamorolone appears to have a much better side effect profile than traditional glucocorticoids, even at the highest doses tested.”

“Although this particular trial was not placebo-controlled, I am encouraged by the safety and efficacy data and look forward to results from the larger placebo-controlled trial(VBP15-004) that is currently underway at Duke and other sites, which could lead to FDA approval,” Smith says.

After completing the one-year VBP15-004 trial, one of the first patients to enroll remains on vamorolone through an expanded access program and continues to be assessed by Smith twice a year.