Started as a task force in 2013, Duke’s Opioid Safety Committee is now an integral and permanent entity within Duke Health, ensuring compliance with state legislation and initiating actions aimed at curbing the nationwide opioid epidemic.

“Duke is part of a growing movement among practitioners and researchers to study and address the different aspects of the epidemic,” says Lawrence Greenblatt, MD, co-chair of the committee. “This is a whole new world for health care providers.”

One ongoing initiative involves studying postoperative outcomes, educating patients, and helping surgeons right-size opioid prescriptions. Padma Gulur, MD, the medical director of Duke’s Perioperative Pain Care Clinic and a member of the safety committee, leads the effort.

“This is an important initiative that we launched in collaboration with our surgeons because one of the most significant issues that has come from the epidemic is that unused drugs are making their way out into the community through a patient’s family and friends,” she says.

Starting with specialties that typically result in a large amount of postoperative pain medication, including urology, obstetrics, and neurosurgery, Gulur’s team asked patients how much of the medication they actually used to control pain following their surgery. “Some patients used some of the drugs and some didn’t use any, but very few needed all of the medication prescribed,” she reports.

The initiative is resulting in recommendations to surgeons on the appropriate amount of medication needed to control pain for the vast majority of their patients as well as improving patient education. “Some patients think they’re supposed to use all of their pain medication and don’t understand the meaning of taking it as needed. We’re working to educate patients better about managing their pain as well as proper storage and disposal of excess medications,” says Gulur.

One of the ways North Carolina is working to address the epidemic is through the Strengthen Opioid Misuse Prevention Act of 2017 (STOP Act), which regulates the amount of opioid therapy that can be prescribed for acute, chronic, and postoperative pain.

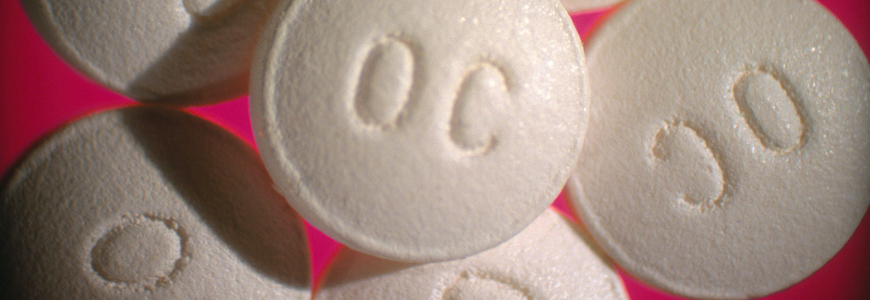

Greenblatt says the STOP Act has resulted in significant changes in prescribing at Duke through a number of initiatives. “We anticipated the legislation, so we were prepared with messaging to all prescribers and changes to the defaults in our EHR system.” For example, when providers select oxycodone for a new prescription for acute pain, the system defaults to a five-day supply, driving behavior for prescribing fewer opioids.

Based on information from Duke’s alliances with community leaders, legislators, law enforcement agencies, and prison systems, Greenblatt paints a sobering picture of how the epidemic is expanding in new ways: “The supply of illicit opioids is plentiful and purer than ever. The vast majority of heroin sold in North Carolina now is mixed with fentanyl, which is up to 40 times more potent and leads to a larger number of overdoses. We’re also seeing a large increase in infections from injecting drugs, including hepatitis C and bacterial endocarditis, as well as addiction-related mental health issues. Conditions we rarely saw in the past are becoming commonplace.”

Gulur recommends that providers not only warn patients about the risks of opioids to their health but that they also give patients a safe space to talk. Sometimes patients know that a family member is stealing their medications, and sometimes they’re victims of domestic abuse as a result, so they feel ashamed. “It’s important that we give them an opportunity to speak candidly, offer resources, and empower them to protect themselves, their families, and their communities,” she says.

“There’s no question that drug dealers need to be shut down,” says Greenblatt, “but, as health care providers, we need to think about the role we can play in driving down demand through education and making resources and treatments widely available.