An advanced reconstructive surgery approach that uses a titanium implant to connect prostheses directly to bone improves mobility, reduces pain, and improves proprioception.

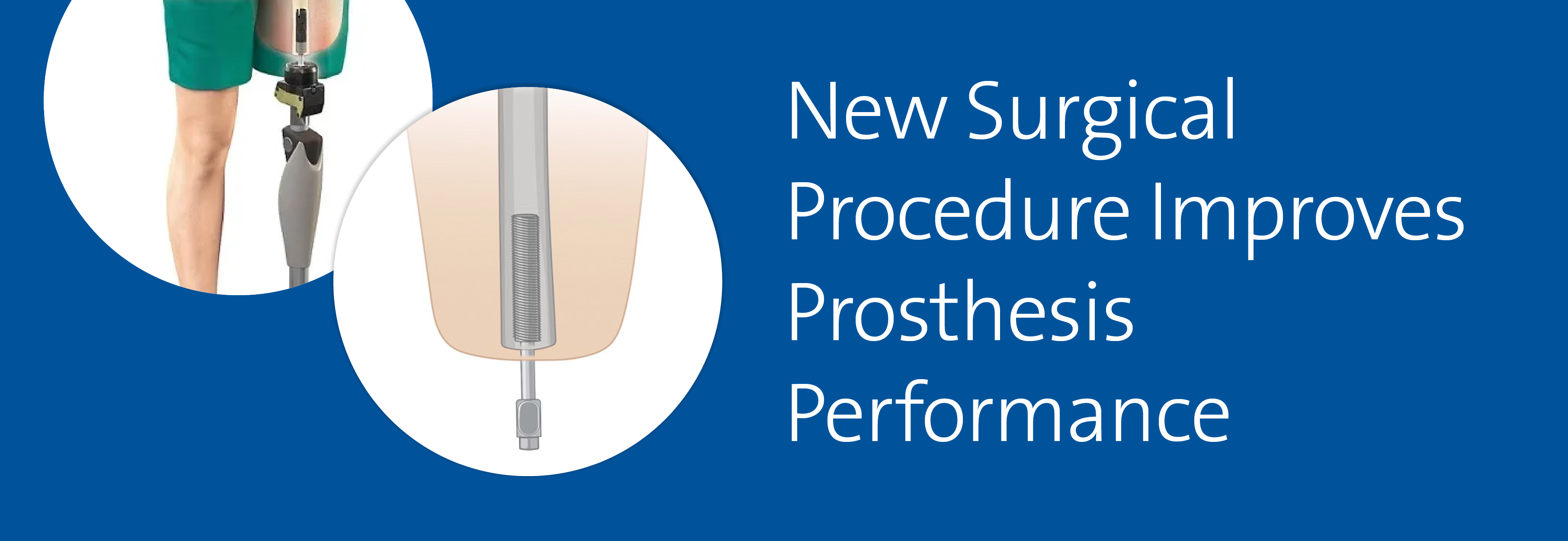

The technique is known as osseointegration because the implanted titanium anchor becomes integrated into the bone of the residual limb. A titanium spike extends out through the skin where the prosthesis can snap on.

This attachment of the prosthesis directly to the skeleton provides the patient with the sensation of movement lacking in a traditional soft-tissue socket-attached prosthesis, according to Will Eward, MD, DVM, an orthopaedic surgical oncologist at Duke.

“Your bones carry a lot of your sensory feedback to your brain. When you have a conventional amputation, where you have a fleshy stump that gets pushed into a socket, learning to walk again can feel like walking on stilts,” Eward says. “The implant restores the feedback to the patient, with the sensation transmitted directly through the bones.”

The technique overcomes another major drawback of the traditional socket suspension approach. A prosthesis will often no longer fit a socket built of muscle, fat, and skin after the patient gains or loses muscle or fat, as commonly occurs during recovery from an injury. Other benefits of osseointegration include reduced skin irritation and pressure sores, improved range of motion, and enhanced comfort.

Eward says that osseointegration was conceived by Swedish a surgeon who was trying to find a solution for amputated limbs that are too short to even create a socket. The technique was first used with military veterans, and the FDA approved the Osseoanchored Prostheses for the Rehabilitation of Amputees (OPRA) Implant System (Integrum AB) for use in above-the-knee amputations in 2020. Its application quickly spread to off-label uses such as with arms and fingers.

The most common use has been in veterans with war wounds, but Eward has treated people who have lost limbs a wide variety of causes, including car crashes, infections, gunshots, diabetes, and cancer.

Eward notes that as orthopaedic surgical oncologists accustomed to operating on bones and trying to save limbs, he and his colleagues Brian E. Brigman, MD, PhD, and Julia Visgauss, MD, “have the baseline training that makes this procedure right in our wheelhouse.”

Duke is one of a handful of centers around the country other than Veterans Administration hospitals that offer the technology.