Successful Diagnosis and Treatment of Rare Eye Disorder

In June 2014, a 35-year-old woman came to Duke Eye Center with a 10-year history of intermittent episodes of double vision accompanied by a jumping sensation in her left eye. These episodes were severe enough to interfere with her work as a nurse. Prior to coming to Duke, she had seen multiple ophthalmologists and neurologists who were unable to provide her with a diagnosis or relieve her symptoms. She had been evaluated for multiple sclerosis and seizure disorders, but an MRI was negative for any abnormalities. It was suggested that her symptoms were possibly a migraine variant.

The patient first saw Anupama Horne, MD, an eye specialist at Duke who was fortunate enough to examine the patient while she was experiencing symptoms. Horne was able to observe abnormal movements of the left eye and record a video of them while conducting a slit lamp examination. Horne suspected an atypical eye-movement problem and referred the patient to her colleague at Duke, neuro-ophthalmologist M. Tariq Bhatti, MD.

“What the video shows is her left eye literally twitching; it’s a type of tremor. You can see the eye rotating,” Bhatti commented. “These are very small movements—if you were just looking at her with the naked eye, you probably wouldn’t even notice it.”

What condition was diagnosed?

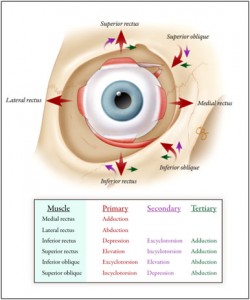

Figure 1. Extraocular muscles and their actions.

(Click on image to view a larger version.)

Answer: The patient received a diagnosis of superior oblique myokymia.

Upon viewing the recording and examining the patient, Bhatti felt certain that superior oblique myokymia (SOM), a rare eye disorder, was the correct diagnosis. “I’ve been in practice for 15 years, and I can count on only one hand the number of people I have diagnosed with SOM,” Bhatti said.

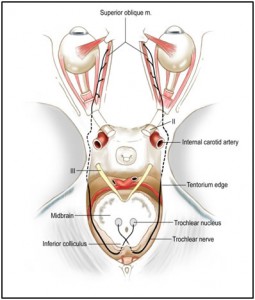

SOM is a neuromuscular disorder of unknown etiology involving the superior oblique muscle, one of 6 extraocular muscles that are responsible for eye movements (Figure 1). SOM was first described in the 1970s as rapid, small-amplitude, rotary microtremors limited to one eye in otherwise healthy individuals. Although the cause is unknown, symptoms are believed to arise from irritation to the 4th cranial (trochlear) nerve that innervates the superior oblique muscle (Figure 2) or to the muscle itself, but the condition appears to have a benign course. A key aspect of diagnosis is obtaining an MRI to exclude any structural abnormalities or space-occupying lesions, Bhatti said.

Bhatti discussed potential treatment options with the patient. Although some patients simply adjust and opt for no treatment, this patient’s symptoms were interfering with activities of daily living and her work. Noninvasive treatments for SOM have primarily focused on antiseizure medications, such as carbamazepine, gabapentin, and clonazepam, he explained, but these medications can cause profound sedation.

Figure 2. Course of the trochlear nerve originating in the midbrain and terminating at the superior oblique muscle. Reprinted with permission from Bhatti MT, Schmalfuss I. Handbook of Neuroimaging for the Ophthalmologist. London: JP Medical Ltd, 2014.

(Click on image to view a larger version.)

The N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist memantine has also been used off label to treat SOM. Additionally, some physicians have injected Botox directly into the superior oblique muscle. A more invasive surgical approach involves microvascular decompression of the trochlear nerve, in which a small sponge is inserted between the nerve and blood vessels of the posterior circulation with the goal of stabilizing the nerve to prevent irritation. Other surgeons have attempted to reposition the muscle itself or weaken it. Bhatti advised against surgery if at all possible, however, because of potential complications.

While discussing treatment options, Bhatti recalled a study he had read about the use of topical beta-blockers to treat SOM. “I said to her, why don’t we try beta-blockers first? It involves just applying a couple of drops a day,” he said. “I had never tried it before on any of my patients, but it seemed to be the most benign approach.”

The patient called within a few days to say that the beta-blocker drops had alleviated her symptoms completely. “We don’t know exactly how the beta-blocker works, but it seems to stabilize the membrane of the nerve or the muscle,” Bhatti said. The patient has continued to be free of symptoms since June, except in times of significant stress, and she simply applies more drops on those days.

Bhatti commented that the key to making the diagnosis in this case was to listen to the patient. “When you have unique symptoms, they are often caused by a unique diagnosis. It’s important to keep an open mind and sometimes do some extra research,” he explained. Bhatti also said that condition can be difficult to diagnose in patients who have intermittent symptoms. If ocular symptoms happen at home, Bhatti advises patients to have a loved one look carefully at the eyes—and even record a video of it with a cell phone or camera. “That can help secure the diagnosis,” Bhatti said.