Study Clarifies Best Treatments for Rare Kidney Cancers

|

|

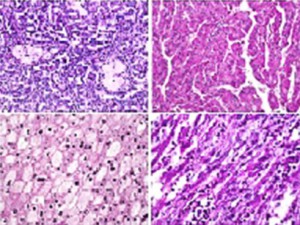

| Figure 1. Cellular differences across non–clear-cell kidney cancer subtypes (top left, type 1 papillary kidney cancer; top right, type 2 papillary kidney cancer; bottom left, chromophobe kidney cancer; bottom right, poorly differentiated sarcomatoid kidney cancer) | |

A head-to-head comparison of 2 biologic therapies used to treat a subset of advanced kidney cancers demonstrated the preferred first-line treatment option. The study was led by researchers at the Duke Cancer Institute, including Andrew J. Armstrong, MD, Daniel J. George, MD, Susan Halabi, PhD, and Samuel Broderick, MS, and is the first and largest to compare the effectiveness of treatments used for metastatic non–clear-cell kidney cancers. This group of malignancies accounts for nearly 20% of kidney cancers.

“We have had very little evidence to guide clinical decision making and drug choice for patients with non–clear-cell renal cancer,” notes Armstrong, who is co-director of the Genitourinary Oncology Research Program at the Duke Cancer Institute and the lead author of the study presented last June at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. “These cancers,” he continues, “are actually very different diseases, with different genetics, so we cannot have a one-size-fits-all approach.”

In their study of 108 participants, the authors focused on various forms of non–clear-cell kidney cancers (Figure 1). The study participants were randomly assigned to receive either everolimus or sunitinib until tumor progression.

Overall, sunitinib was found to be superior to everolimus at prolonging the amount of time before tumors regrew, but it had a higher rate of severe toxicity than everolimus. Sunitinib was also more effective for the treatment of papillary-type kidney cancers as well as for those with better prognoses. Study participants with chromophobe and poor-risk disease characteristics who were treated with everolimus had a longer rate of median progression-free survival than those treated with sunitinib.

“These drugs have different mechanisms of action, so it makes sense that they would have different response rates for these tumors,” elucidates Armstrong, noting that the diseases are essentially genetically different. He adds, “This information provides physicians with sound data to guide treatment for their patients based on the type of cancer identified.”

More than 100 participants also donated tumor tissue, thus establishing the largest repository of non–clear-cell kidney cancer tissue. This tissue bank will aid in the development of new drugs and the future identification of biomarkers for the disease.