Social determinants of health (SDOH) are well recognized as factors that affect health outcomes, but a Duke endocrinologist wants to encourage physicians to ask their patients to provide more complete social histories and to intervene, if possible, with those who face significant risks.

Susan E. Spratt, MD, a Duke endocrinologist and diabetes specialist, advocates for the creation of more structured workflows to allow physicians to identify such risks as inadequate housing or food source limits and incorporate them into patient records as part of a complete health assessment. For physicians treating patients with diabetes, social determinants can be indicators of patients’ compliance with nutritional and insulin dosing directives.

“Many specialties may look at a single health issue, but in diabetes care, we want to know about diet and exercise and the effects diabetes has on vision, foot care, blood, and heart. Many factors play a significant part of our patient assessment,” says Spratt.

Spratt says that physicians and clinical staff are aware of the consequences of social health determinants. Many health systems, including Duke Health, have already incorporated SDOHs into EHRs. “But few, if any, understand how to create a workflow to capture this information about our patients,” she adds. “I suspect that we don’t know what we are missing.”

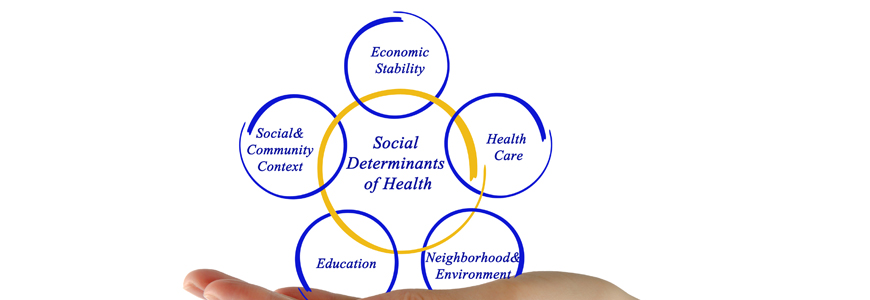

SDOHs are nonmedical, Spratt notes, but they affect hospitalization and emergency department use, patient readmission, and chronic disease management. Spratt divides social determinant assessments into four groups:

- Socioeconomic factors: Access to safe housing, healthy foods, transportation, and utilities (heat, electricity, water).

- Physical environment: Location of housing, freedom from gun violence, lead-poisoning risks in plumbing, safe places to walk and/or exercise.

- Social factors: Risks of depression, domestic violence, or social isolation.

- Behavioral risks: Use of cigarettes, illegal drugs, or alcohol abuse.

The key concern, Spratt says, is that use of the SDOH data varies by provider, clinic, and patient. “We need a systematic way to collect this data and make sure it becomes part of the work of the clinic. It’s not realistic to place the burden on the physician to be the data gatherer, data entry clerk, and social worker for every patient,” she says. “A team approach is needed to gather and enter data, which is reviewed by the provider, and then triaged to someone trained to connect these patients to resources.

“The second issue is not specifically related to questions and answers recorded in a database, but about the need to understand our patients on a personal level,” Spratt says. “We need to know how they are feeling, what motivates them, who is in their lives, and who is not.”

Increasing Recognition of Social Determinants of Health

Recognition of SDOHs as an indicator has been rising in recent years. In 2019, the World Health Organization created a new initiative to study determinants and potential interventions. WHO research has demonstrated that socioeconomic factors are more significant than health behaviors or environment in predicting outcomes.

In North Carolina, NCCARE360 is the first statewide coordinated care network attempting to connect those with identified needs to more than 1,100 community resources. The organization also provides a feedback loop via the electronic connection. But the resource is not yet fully accessible, says Janet Prvu Bettger, PhD, associate professor in the School of Medicine.

Bettger leads an initiative to recruit and train undergraduates to become community health navigators as part of her collaboration with Spratt to ask patients about social determinant risks and follow-up to provide resources.

The Duke undergraduate effort, which requires extensive candidate screening and training, prepares students to record social histories and follow-up with patients to connect them with community resources. Now conducted by phone as a results of COVID-19, the program has prepared a comprehensive resource guide for patients and providers.

As SDOHs become more integral in health interventions, Spratt says, outcomes for high-risk patients may improve. “You want the best outcome for these patients,” she says. “Understanding the socioeconomic factors will help us as providers.”