The molecular pathobiology of uterine fibroids has remained elusive for researchers, despite decades of basic and translational studies. As a result, treatment options are limited for the 70% to 80% of women who will likely develop fibroids by age 50.

In a Duke study published in April 2019 in PLOS ONE, researchers demonstrated evidence of biomechanical and collagen heterogeneity in fibroids. Increased awareness of these differences— and intentional consideration of them when designing studies and interpreting data—will lead to a better understanding of fibroids’ pathophysiology and could lead to improvements in therapies, according to senior author Friederike Jayes, DVM, PhD, assistant professor in Duke’s Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology and a specialist in the physiology and endocrinology of the female reproductive system.

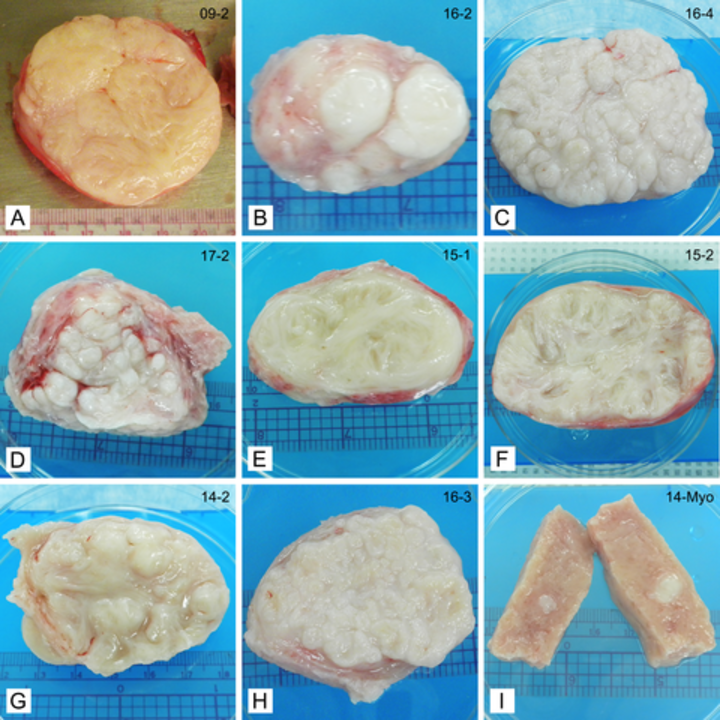

The study focused on the structure, collagen content, and tissue stiffness of 19 uterine fibroids in eight women, with samples taken from different regions within the fibroids. Differences were discovered that could be associated with variations in local pressure, biomechanical signaling, and altered growth, as shown in the figure below:

“Physicians have traditionally used the location and size of fibroids as the main classification for them, but with this study, we have clearly demonstrated that large structural variability exists between different fibroids, even within the same woman’s body,” Jayes reports.

“Clinicians have been puzzled for years about why some women get no fibroids, some women get one large fibroid in their lifetime, and yet other women will have multiple small fibroids throughout the uterus that keep growing over time and will grow back when removed,” says Duke ob-gyn MargEva Cole, MD. “There’s also a difference in when they occur—some women develop them in their 20s and others not until their 40s—which makes a difference in reproductive outcomes.” Cole notes that differences in how patients of various ethnicities are affected have also been identified, and studies like this one will help physicians understand the reasons for these differences.

Most studies do not report what portion of the fibroid was studied, Jayes explains. This makes it difficult to compare results of studies, hinders understanding of fibroid physiology, and impedes the development of appropriate treatment strategies. For some time, obstetricians and gynecologists have been seeking non-surgical treatments for fibroids in order to preserve fertility. This study shows that recognizing and understanding the variation in these tumors is needed if this goal is to be obtained.

Jayes notes that most surgical options result in a woman being unable to have children. “We hope that studies like ours will lead the way to nonhormonal, uterus-preserving treatments,” she says.

“We need to counsel patients effectively on their options for treating their fibroids,” Cole adds. “We discuss the options of leaving them in place, removing or ablating them during surgery, or embolizing them with noninvasive vascular techniques. We consider all the approaches with each patient, but it would be very helpful to know if certain fibroids would be more responsive to a particular therapy so we could give the patient more personal, individualized counseling.”

“There’s still so much we don’t know about these very common and often painful tumors,” says Jayes, “but the differences we found in our study are compelling. There will probably never be one treatment that’s right for every fibroid and every woman, but with well-designed research we can learn more about how they form and grow and which treatments would work best on which type of tumor.”