RCC With Vena Cava Thrombosis

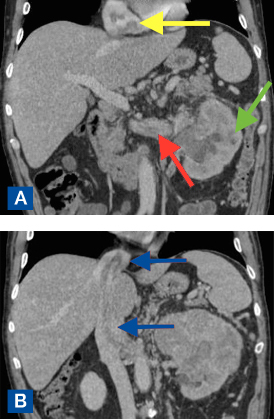

FIGURE 1A–B. Coronary computed tomography angiogram on initial presentation. (A) Yellow arrow shows right atrial tumor thrombus. Green arrow shows a large, left renal mass. Red arrow depicts left renal venous tumor thrombus. (B) Blue arrows show inferior vena cava tumor thrombus extending into right atrium

An active, otherwise healthy, 63-year-old man from South Carolina was referred to a urologist after presenting to his primary care physician with anemia, low back pain, and hematuria. Computed tomography (CT) revealed a large renal mass with inferior vena cava (IVC) tumor thrombus and intracardiac tumor thrombus (Figure 1).

Recognizing that few places offer curative treatment for renal cell carcinoma (RCC) with intravascular tumor thrombosis, the urologist referred the patient to Duke Urology.

Question: What treatment could Duke offer the patient, and what was his outcome?

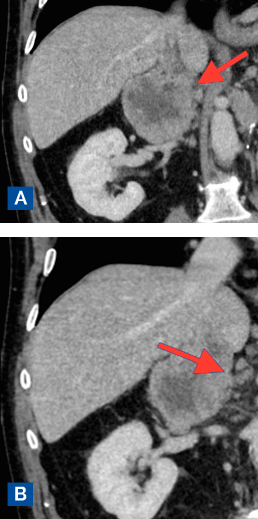

FIGURE 2A–B. Coronary computed tomography angiography showing a new tumor on the contralateral adrenal gland. (A) Red arrow indicates large, right adrenal metastasis with intrahepatic inferior vena cava tumor thrombus. (B) Red arrow indicates large, right adrenal metastasis

Answer: The patient underwent radical nephrectomy with IVC thrombectomy and vascular reconstruction. Because of the intracardiac tumor thrombus, the surgery also required cardiopulmonary bypass. Six months later, when CT revealed a new tumor in his contralateral adrenal gland (Figure 2), again with vena cava involvement, the patient underwent repeat IVC thrombectomy with vascular reconstruction that involved resection of the IVC and interposition replacement. Almost 1 year later, the patient remains in complete remission.

Although radical nephrectomy, with IVC thrombectomy and vascular reconstruction, is the only potentially curative treatment for RCC with IVC thrombosis, the procedure is being performed less and less, potentially because of the availability of medications for metastatic kidney cancer, says Edward Rampersaud, MD, the urologic oncologist who performed the surgery.

“The number of these operations being performed started to drop off in 2005 when targeted medications first became available,” he notes. “People likely felt more comfortable writing a prescription than performing a complex, invasive surgery they may not have much experience with.” But that’s a mistake, he says: Medical intervention in these circumstances is never curative, whereas surgery is curative 50% to 60% of the time.

In fact, the patient's original plan was to enroll in a clinical trial with the urologist in South Carolina after undergoing surgery at Duke to remove as much of the tumor as possible. However, after the first surgery, there was no evidence of tumor, so the patient didn’t require immediate additional intervention.

Still, the patient’s case was challenging because reoperative surgery requires that the surgeon operate through scar tissue from the previous procedure. In addition, although the patient’s tumor was a level 3 thrombus, he opposed repeat sternotomy, so Rampersaud performed the surgery via a thoracoabdominal approach, which required dividing the diaphragm to grant intraperitoneal access and suprahepatic caval control.

The surgery is stressful, Rampersaud admits, but, he argues, it is critical that it continue to be offered to patients with RCC and IVC thrombosis: “We have to recognize that, even though these patients have a disease that’s significantly advanced, they need to be evaluated for the possibility of surgery. With this surgery, 5-year mortality drops from 100% to 40%—that’s a huge difference, especially for the 60% who live.”