A Rare Retinal Disorder Mimics AMD

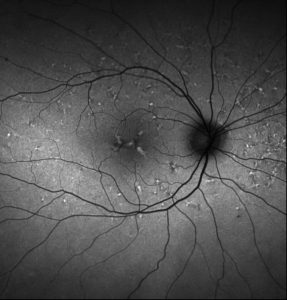

Fundus autofluorescence of the right eye showing hyperautofluorescence corresponding to the yellow lesions.

A 40-year-old woman consulted her local ophthalmologist after noticing visual distortion while reading, difficulties with her night vision, and sensitivity to light. Although the patient’s visual acuity was good—20/20 in her right eye and 20/25 in her left—her presentation was concerning for age-related macular degeneration (AMD), a condition known to have affected other family members, and she was referred to the Duke Eye Center for further work-up.

At Duke, a retinal specialist observed that the patient’s clinical presentation differed slightly from typical AMD and might instead be a genetic disease that mimics AMD. He referred her to Alessandro Iannaccone, MD, MS, the director of the Center for Retinal Degenerations and Ophthalmic Genetic Diseases at Duke.

Question: Iannaccone ultimately recommended a therapy commonly used to treat exudative complications from AMD. Why was it still beneficial to confirm that the patient’s condition was a pattern dystrophy rather than AMD, even if the treatment protocol did not change?

Answer: Because pattern dystrophies are autosomal dominant diseases, it is important that patients are given the opportunity to undergo molecular genetic diagnostic testing and genetic counseling to discuss the risks for both themselves and their children. Gene therapies for pattern dystrophies are also likely to become available in the future, whereas this is not presently anticipated for AMD, which is a complex, multigenic disease.

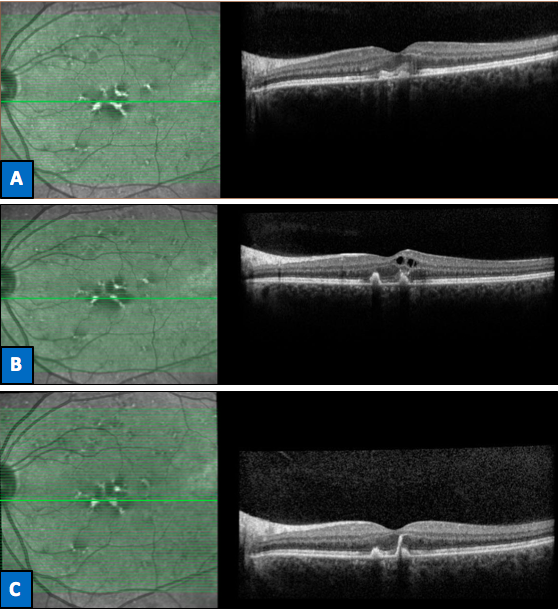

FIGURE. Red free photography (left column) and optical coherence tomography (right column) of the left eye. A) Subretinal hyperreflective foci corresponding to neovascular buds at initial consultation (Vision: 20/25). B) Formation of cystic intraretinal fluid cavities due to leakage from the neovascular lesion 3 months later (Vision: 20/70). C) Resolution of the fluid after treatment with intravitreal anti-VEGF injections (Vision: 20/20).

Even though Iannaccone would use the same treatment for both AMD and retinal dystrophy, distinguishing between the 2 offers other benefits, he says: “Not only are the diagnoses intrinsically different, but there’s also a reproductive risk that’s very different. This patient is still in childbearing age range, and she has a daughter, who we now know has a 50% chance of developing the same problem. We can’t make those kind of predictions for people with AMD.”

When the patient presented at Duke, both Iannaccone and the retinal specialist observed deposits in the macular region of the patient’s eye at the level of the retinal pigment epithelium shaped in a spokewheel pattern radiating out from the central part of the macula—an unusual clinical presentation that was suspicious for butterfly-shaped pattern dystrophy. The patient’s family history also suggested a predictable, autosomal dominant mode of inheritance of macular degeneration that is not usually observed for AMD.

Iannaccone ordered a molecular genetic diagnostic test to assess a panel of genes previously implicated in pattern dystrophies. Based on the patient’s metamorphopsia and previous reports of butterfly-shaped pigment dystrophy in the literature, Iannaccone suspected that the patient might develop neovascular exudative complications. He taught her how to use the Amsler grid test to monitor her vision and told her to come in if her vision worsened significantly.

Several weeks later, her vision worsened and she returned. The visual acuity in her left eye had decreased to 20/80, and imaging revealed that she had developed a neovascular lesion reminiscent of retinal angiomatous proliferation.

With the genetic test results still being processed, the patient’s diagnosis was unclear, but Iannaccone decided to treat the exudative complications using a VEGF inhibitor, the standard of care for AMD.

“We were pretty sure she had a pattern dystrophy rather than AMD, but she was having an exudative complication identical to what we see in AMD patients, and this is a treatment we know is effective,” Iannaccone explains.

After the patient began treatment, molecular testing confirmed a diagnosis of butterfly-shaped pattern dystrophy caused by a Peripherin/RDS mutation—the gene most commonly involved in pattern dystrophies. The rare specific mutation affecting the patient had been reported only twice in the literature, but in both reports it was associated with neovascular complications.

“If I had known from the beginning what the mutation was, I would have had an even higher concern for this complication,” Iannaccone says. “Fortunately, we erred on the side of caution and used a common sense approach, treating her correctly.”

The patient started responding to treatment immediately, and now, after 4 injections, her visual acuity is again 20/20, the fluid inside the retina is gone, and the lesions associated with her pattern dystrophy are shrinking (Figure).

“Historically, we didn’t really have anything to offer patients with pattern dystrophies,” Iannaccone notes. “So it’s rewarding to see that they can respond to the treatments we use for AMD. In our research, we’re actually increasingly seeing that the things we’re learning about more common retinal diseases like AMD may also prove valuable to retinal dystrophies.”