Rare Diagnosis Following Cascading Decline in Kidney Function

A 45-year-old woman with a history of cystinuria and recurrent renal calculi presented to an urgent care center with persistent cough and skin infection. Physicians suspected drug toxicity and dehydration, so they adjusted her prescriptions. Laboratory values indicated new-onset renal insufficiency.

A 45-year-old woman with a history of cystinuria and recurrent renal calculi presented to an urgent care center with persistent cough and skin infection. Physicians suspected drug toxicity and dehydration, so they adjusted her prescriptions. Laboratory values indicated new-onset renal insufficiency.

The patient’s cough and skin condition showed improvement at a follow-up visit, but laboratory test results revealed hematuria, proteinuria, and persistent renal failure. The patient, who was taking angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors for hypertension and had experienced numerous allergies to medications, was referred to Duke Nephrology.

Question: How did Duke nephrologists identify the patient’s unusual condition?

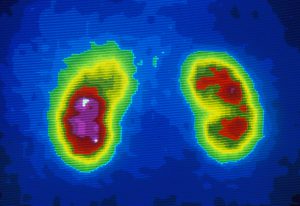

Answer: After interviewing the patient, reviewing her medical history, and performing microscopic urinalysis, the nephrology team performed kidney biopsy, which confirmed the presence of glomerular basement membrane antibodies—a definitive marker of Goodpasture syndrome.

The decision to perform kidney biopsy was an unusual choice at such an early juncture, but it proved to be the diagnostic key, says John P. Middleton, MD, the attending Duke nephrologist and director of the Duke Division of Nephrology’s site-based clinical research.

The hematuria and proteinuria levels could have been interpreted as a straightforward urinary tract infection, Middleton says. But both were clinically significant in his differential diagnosis.

“We initially believed the situation was likely to be an unusual presentation of a common disorder—more kidney stones or additional medication allergies or perhaps a straightforward urinary tract infection,” Middleton says.

But when ongoing laboratory tests continued to indicate renal dysfunction, the nephrology team began to suspect an underlying, undiagnosed condition, says Jessica Morris, MD, a Duke nephrology fellow who worked closely with the patient.

The advanced stage and activity of the patient’s Goodpasture syndrome as well as the pathologic antibody were evident on biopsy findings, says Middleton. “Early on, we could see her kidney function crumbling before our eyes,” he says. “It was a situation that required an immediate response.”

The case was unusual because the patient did not experience any warning signs such as Goodpasture syndrome–related lung involvement, which is common to the condition. Middleton initiated aggressive treatment with oral cyclophosphamide and plasmapheresis to lower the patient's risk of lung complications.

After being hospitalized for more than 40 days, the patient’s acute decline in kidney function was halted. Because of the effects of Goodpasture syndrome, however, she is still being treated for advanced-stage kidney disease. A few months after leaving the hospital, she was assessed and placed on the waiting list for transplant.

Duke nephrologists see several cases a year, Middleton says. “One of the reasons Goodpasture syndrome is so difficult to diagnose is because it is so rare. We don’t have data from large, randomized clinical trials and clinical outcomes from thousands of patients.”

Middleton cautions that cases of unexplained decline in kidney function should be referred to a major center, particularly if the problem doesn’t resolve with early clinical maneuvers. “To manage this condition effectively, the patient is best treated at a center that has immediate access to multispecialty consultations and multiple treatment modalities,” he says. “It’s essential to have many specialists reviewing the clinical data.”