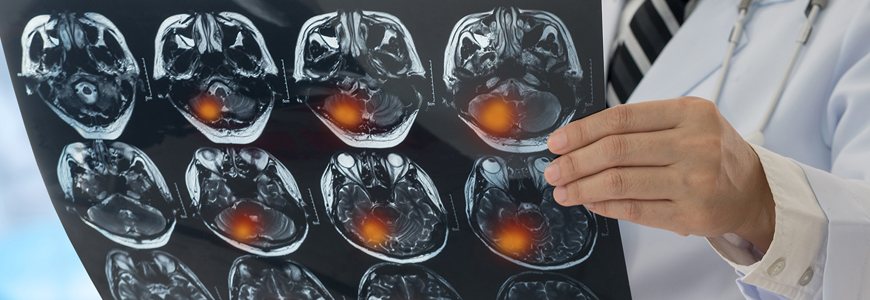

Researchers are leveraging Duke’s long history of studying the molecular underpinnings of childhood brain tumors and exploring innovative techniques of developing vaccines and other therapies that target specific mutations.

In clinical trials underway or beginning soon, researchers are identifying mutations that drive low-grade childhood tumors such as pilocytic astrocytomas and applying therapies that target the mutations.

David Ashley, PhD, MBBS, director of pediatric neuro-oncology and the Preston Robert Tisch Brain Tumor Center says that these targeted agents are starting to make a difference in patient outcomes in clinical trials and have the potential of proving very effective.

“Our research community has done a great job over the past decade to understand the genetic landscape of brain tumors in children and how those mutations and other events work to cause the tumors to form and grow,” he says.

One recent adult study shows promise for children with glioblastoma. In December 2017, the pediatric neurosurgery and neuro-oncology teams at Duke’s Preston Robert Tisch Brain Tumor Center began enrollment for a phase 1b, single-site clinical trial assessing the safety of PVSRIPO—a genetically recombinant, nonpathogenic poliovirus/rhinovirus chimera developed by Duke scientist Matthias Gromeier, MD—in pediatric patients with WHO grade III and IV gliomas.

The study follows promising results from Duke’s phase 1 trial of PVSRIPO in adults with recurrent grade IV gliomas, which demonstrated the safety of the therapy and long-term survival in some patients. Based on the results of the adult trial, investigators are hopeful about the therapy’s potential in pediatric patients. “The exciting experience we’ve had in developing the poliovirus treatment of adult recurrent glioblastoma is now being translated to pediatric brain tumors,” says Ashley, who was the study’s co-principal investigator (PI).

“We think a lot of the efficacy of this therapy lies in the immunogenicity it elicits—the inflammatory response of the patient’s immune system,” explains the study’s co-PI, Eric Thompson, MD, a pediatric neurosurgeon at Duke. “Because children generally have a more robust immune system than adults, we think it’s possible that this therapy will work as well if not better in children compared with adults.”

The trial will enroll 12 patients between the ages of 12 and 18 years and assess safety as a primary outcome measure and 24-month overall survival as a secondary outcome measure. Patients will receive a single dose of PVSRIPO and periodically return for follow-up to monitor tumor status, adverse events, and changes in blood immune profiles. Outcomes will be compared with age- and gender-matched historical controls.

Such studies are much needed in both adults and children with malignant glioma, Thompson says. “There are not currently many good options for these patients. They have received upfront therapy and often other types of therapy as well at recurrence, but typically they ultimately progress.”

Ashley says that although many childhood brain tumors can be successfully controlled with surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy, there’s a substantial subset of tumors that are resistant to these therapies, including high-grade gliomas and recurrent medulloblastomas. “Although we’ve identified specific mutations that cause these tumors, as yet we haven’t found therapies that are making a meaningful impact on outcome. These are the tumors we’re focusing our energy on at Duke right now,” he says.

Other studies underway include using a peptide vaccine approach to target viral antigens that appear in tumors and using dendritic cells—immune cells that are educated to help the immune system respond to antigens—to target mutations.