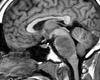

Treatment with a genetically recombinant, nonpathogenic poliovirus/rhinovirus chimera (PVSRIPO) developed at Duke Cancer Institute (DCI) significantly improves long-term survival in patients with recurrent WHO grade IV malignant glioma, according to results of a phase 1 clinical trial.

Treatment with a genetically recombinant, nonpathogenic poliovirus/rhinovirus chimera (PVSRIPO) developed at Duke Cancer Institute (DCI) significantly improves long-term survival in patients with recurrent WHO grade IV malignant glioma, according to results of a phase 1 clinical trial.

In the trial, patients receiving PVSRIPO had a three-year survival rate of 21 percent compared with just 4 percent for a historical control cohort of patients treated at Duke. Results were published in The New England Journal of Medicine in June 2018.

“Glioblastoma remains a lethal and devastating disease, despite advances in surgical and radiation therapies, as well as new chemotherapy and targeted agents,” says the study’s senior author, Darell D. Bigner, MD, PhD, director emeritus of The Preston Robert Tisch Brain Tumor Center at Duke.

“There is a tremendous need for fundamentally different approaches,” he says. “With the survival rates in this early phase of the poliovirus therapy, we are encouraged and eager to continue with the additional studies that are already underway or planned.”

PVSRIPO, developed by Matthias Gromeier, MD, professor in the Duke Department of Neurosurgery, member of DCI, and co-lead author on the study, works as a potent intratumoral immune adjuvant to generate tumor antigen–specific cytotoxic T-cell responses. The therapy’s mechanism of action was published in late 2017 in Science and Translational Medicine.

The phase 1 trial was launched in 2012 and had a median follow-up of 27.6 months for patients receiving PVSRIPO. Initially, survival in the two groups was comparable, but, at two years after treatment, the survival curves diverged: Patients receiving PVSRIPO had an overall survival of 21 percent versus 14 percent for the historical controls. At three years, the gap widened further, with a survival rate of 21 percent for patients receiving PVSRIPO, compared with 4 percent in the control group.

For all 61 patients receiving the poliovirus, the median overall survival was 12.5 months, compared with 11.3 months for the historical control group.

“Similar to many immunotherapies, it appears that some patients don’t respond for one reason or another, but if they respond, they often become long-term survivors,” says co-lead author Duke neuro-oncologist Annick Desjardins, MD. “The big question is, ‘how can we make sure that everybody responds?’”

Combining the poliovirus with other approved therapies is one approach already being tested at Duke to improve survival. A phase 2 study now underway combines the poliovirus therapy with the chemotherapy drug lomustine for patients with recurrent glioblastomas.

New trials were also started after the therapy obtained “breakthrough therapy” designation from the FDA in 2016. In addition, both a phase 2 trial for malignant glioma in adults and a phase 1 trial for pediatric patients began earlier this year. Some patients with breast cancer or melanoma will soon be eligible to join clinical trials that expand the therapy beyond brain tumors.

The authors reported that 69 percent of study patients had a mild or moderate adverse event attributed to poliovirus as their most severe adverse effect. Low dose bevacizumab was used to help control the localized inflammation of the tumor and its side effects.