In a landmark study published in June 2019 in Health Affairs, researchers found that current and projected workloads for specialty palliative care physicians will be untenable within the next 25 years due to workforce shortages and a growing cohort of Medicare beneficiaries becoming eligible for palliative care.

Senior author Arif Kamal, MD, a medical oncologist and palliative medicine specialist, says this declining ratio of physicians to patients can be mitigated through a series of national health care policy changes and by building the palliative care delivery workforce beyond physicians.

“Palliative care is a philosophy of care,” he says, “and all clinicians can participate in it by building their skills in providing this extra layer of support to their patients with serious illnesses.” Duke’s core palliative care teams comprise physicians, advanced practice practitioners, social workers, and chaplains—all of whom work together to support patients’ physical, emotional, and psychosocial needs.

Fueled by Medicare’s recognition of the field of palliative care, data showing that it can improve survival for patients with advanced cancer, and guidelines from organizations including the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the American Heart Association stating that early integration of palliative care should be considered best practice, it has become the fastest growing clinical service in the U.S., according to Kamal. “Whereas we used to be fearful of extending a patient’s survival at the expense of their quality of life, we now recognize that patients can have both,” he says.

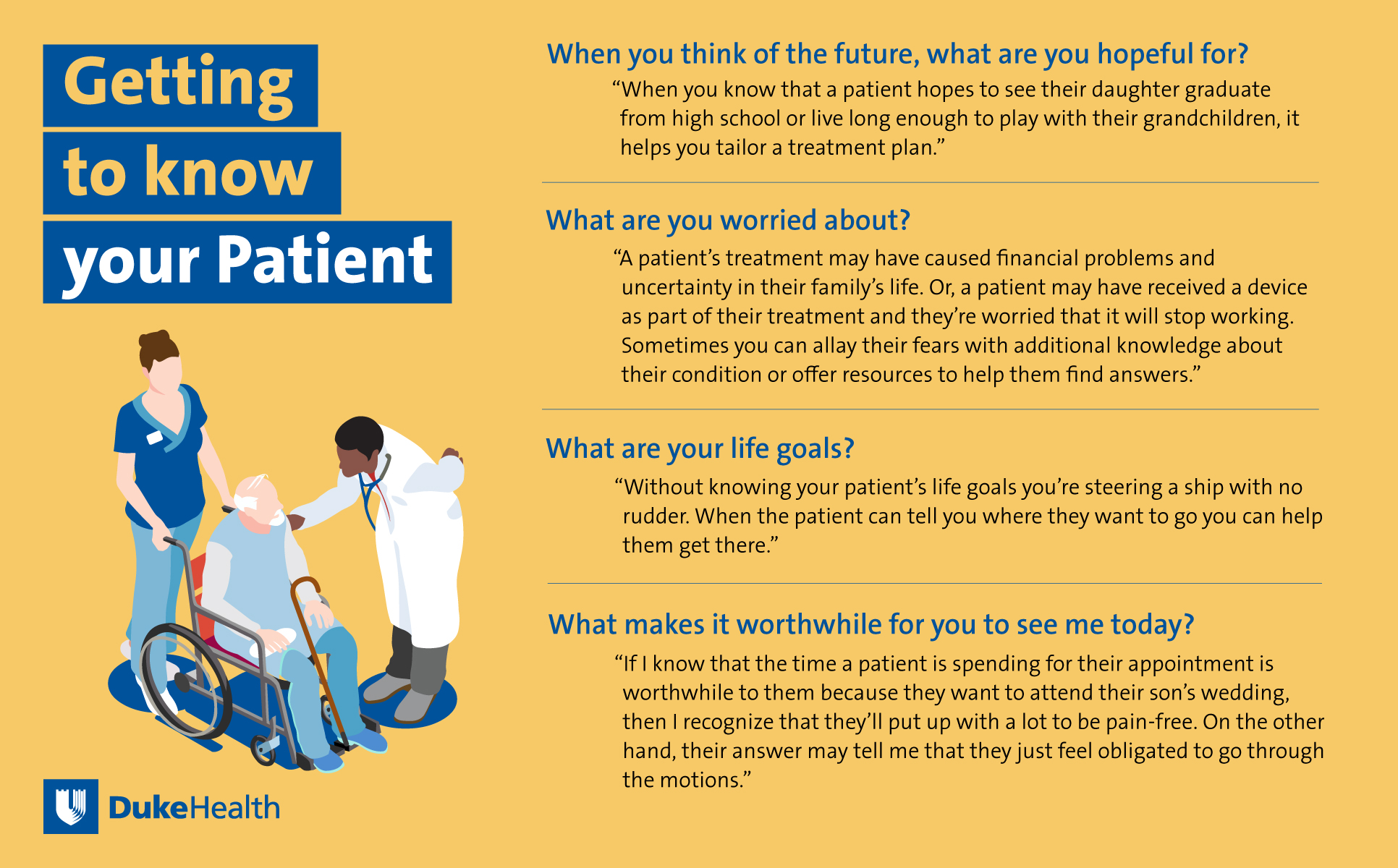

Kamal says he routinely asks his patients a set of questions that helps him better understand patients’ needs as they cope with serious chronic illness. Here are the questions and Kamal’s description of how they can be helpful in getting to know a patient:

Busy schedules, extra time needed for appointments, and simply feeling uncomfortable asking patients these questions are all barriers to clinicians delivering the support that seriously ill patients need, Kamal notes. “If we don’t feel comfortable having these conversations with patients we need to learn,” he advises. “If we already know how to ask the questions we need to practice. If we don’t have time to ask the questions we need to share the responsibility. But the ultimate outcome shouldn’t be that we’re just not going to do it.”

Based on the study results, Kamal says the research team proposed a set of policy solutions, including adoption of the Palliative Care Hospice and Education Training Act, an evolution of Medicare payment models to allow non-physician clinicians to bill for their services, advocacy for a team-based approach to delivery of services, and support for additional research into workforce capacity.