In cases of congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH)—the rare and serious condition in which the diaphragm fails to fuse completely, leaving space for internal organs to move into the thoracic cavity and inhibit normal fetal development—several well-timed evaluations and interventions may be required throughout the pregnancy and post-delivery to address lung, heart, and other possible clinical conditions.

In this Q&A, neonatologist Margarita Bidegain, MD, MHS-CL, and maternal-fetal medicine (MFM) specialist Brita K. Boyd, MD, discuss Duke Children’s CDH program and its comprehensive, individualized, family-centered care for patients with CDH, which affects an estimated 1 in 3,600 babies born in the United States each year.

Q: What strengths does Duke’s experienced, multidisciplinary team bring to treating babies with this condition?

Bidegain: Our CDH working group meets once a month to determine what extra help each infant with CDH and their families might need prenatally and post-delivery through a detailed review of prenatal labs and exams, fetal MRIs measuring lung volume based on size and gestational age, high-resolution ultrasounds, genetic testing, and fetal echocardiograms. Our active team of clinicians includes pediatric surgeons, neonatologists, cardiologists, radiologists, high-risk MFM specialists, intensive care specialists, and genetic specialists. Patients benefit from our holistic prenatal evaluation program and well-established care protocols for this condition, which enable us to coordinate multiple consultations in one day for patients to meet with the members of our team. By the time the baby is born, we know the baby’s and families’ needs very well and organize our team and management accordingly.

Boyd: Having such a personalized approach for this complicated condition is extremely important. The collaboration of experts and our close communication with referring physicians throughout the pregnancy are crucial and allow everyone to be part of the conversation in terms of care planning and timing of the delivery and surgery. We also try to normalize pregnancy where possible because we don't want our patients to miss out on some of the positive aspects of pregnancy, including discussing delivery preferences and celebrating the pregnancy as it continues. We really try as much as possible to let them continue their routine prenatal visits with their doctors at home.

Q: What are the biggest challenges in establishing individualized treatment plans prior to delivering a baby with CDH?

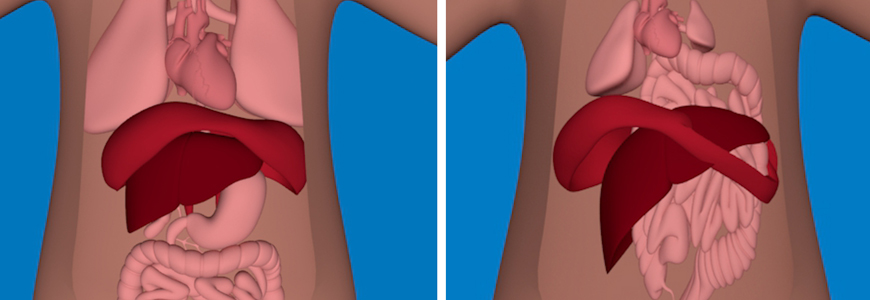

Boyd: In addition to following fetal growth and anatomy during the pregnancy, we continue to assess fetal lung volume as the pregnancy progresses. In babies with CDH, organs such as intestines, the stomach, and sometimes the liver and spleen take up room in the chest, which causes compression and shifting of the heart and lungs. The smaller the lungs are, the more respiratory problems a baby is likely to have after birth; we can’t predict with certainty how sick a baby will be after birth, so we try to prepare parents for a range of outcomes for after a baby is born.

Some babies with CDH also have other birth defects and/or genetic conditions that may complicate their treatment and impact their health. We need to look closely at the whole fetus to evaluate for signs of other birth defects, and we also counsel mothers about the option of prenatal genetic testing. About 10% of babies with CDH will also have a genetic condition, which might impact how they develop after delivery. When we're evaluating the kind of treatment plan a baby may need, it’s especially important to know about any heart birth defect in advance so we can prepare families for that and have a treatment plan in place.

Additionally, delivery planning must be considered carefully. We want to deliver as large and mature a baby as safely possible, but sometimes maternal or fetal health complications require an earlier delivery. After delivery, our surgeons can't operate until the neonatologist and respiratory therapist have stabilized the baby with a ventilator. If we have a baby who needs more oxygen support than a ventilator can offer, our cardiac surgeons and pediatric intensive care specialist may offer extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO).

Bidegain: Due to the severity of potential clinical issues associated with CDH, it is so important to diagnose this condition as early as possible so that our team can determine whether surgery is needed, monitor the baby’s development, and help patients and families understand what the process will be like for them and their child. While the condition typically occurs prenatally and can often be seen in the first ultrasound, it can actually develop at any time in the lifespan. There are some babies with very mild CDH that may not be recognized until later in pregnancy or after delivery.

Q: How does Duke support families after their child is discharged?

Bidegain: One of our biggest resources is our medical home transitions program run by pediatricians and specialized nurse practitioners, who provide follow-up care for families when the baby goes home. Parents have the ability to call 24/7 with any questions and have immediate access to our specialists to determine if they need to go to the ED, clinic, or pediatrician’s office.

Boyd: We also have a wonderful support group in our clinic that can provide individual or group therapy for mothers, fathers, siblings, and other family members, as it's very stressful to go through a pregnancy with a fetal birth defect, and it can be very stressful after delivery, as well.