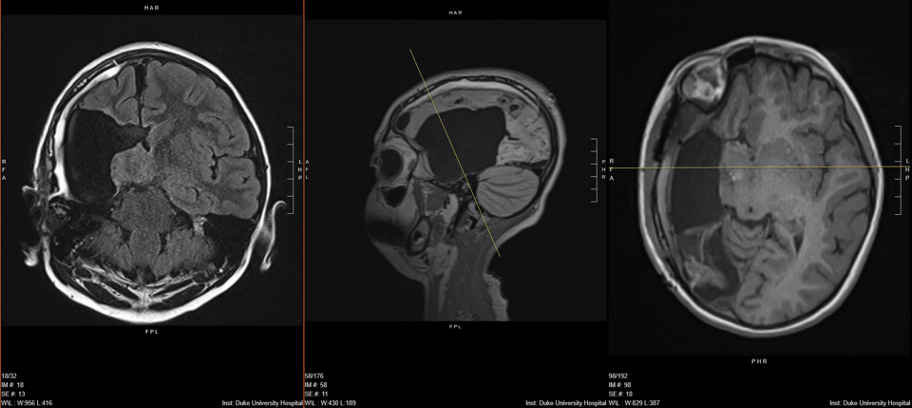

A right-sided, middle cerebral artery (MCA) stroke in utero caused a pediatric patient to begin having epileptic seizures when she was 3 months old. Anti-seizure medications were effective until she reached age 5. But then, with the brain-body connection fully established, her seizures became more frequent and more intense. The refractory nature of the girl’s epilepsy led her parents to seek advanced care at Duke’s Level 4 Epilepsy Center.

At the time she presented to pediatric epileptologist Muhammad Zafar, MD, the patient was 7 years old, and experiencing a few seizures each week. “My concern was that, if we did not treat the epilepsy, she would remain at this 7-year-old mark developmentally. The seizures and medications were impacting cognition and learning; she stopped progressing,” he says. “Unfortunately, medication was no longer effective, so the only option to help her get back on track was curative surgery.”

Question: How did the Duke epilepsy team eliminate the patient’s seizures using functional hemispherectomy?

Answer: Zafar and pediatric neurosurgeon Matthew Vestal, MD, determined the best surgical option was a functional hemispherectomy. A successor to anatomical hemispherectomy, which involves removing the diseased part of the brain entirely, functional hemispherectomy disconnects the epileptogenic portion of the brain, but leaves the tissue in place. This reduces the risk for hydrocephalus.

“When you disconnect the tissue electrically from the rest of the brain, it's still alive and occupying space, so you don’t get the buildup of fluid. But because it's no longer connected to anything, it's just seizing by itself. It can't train the good parts of the brain to have seizures,” says Vestal. “That's the heartbreaking part of these kids getting to us too late. Eventually, the good side of the brain learns to have seizures, and then no amount of surgery can cure them.”

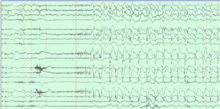

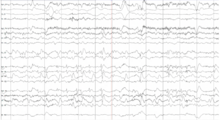

To confirm the patient was a good candidate for functional hemispherectomy, Zafar and Vestal first had to pinpoint the source of the patient’s seizures. The patient was admitted to the Epilepsy Monitoring Unit for video electroencephalography (EEG). Zafar slowly decreased her medications, allowing her seizures to occur in a controlled environment. Video recordings of brain activity captured during multiple seizures revealed that they originated solely in the right side of the brain, confirming the epilepsy team’s hypothesis.

“For kids who start off with a stroke like this little one did, they can easily move functions like movement and language to the healthy side of the brain. This is called neuroplasticity,” says Vestal. “In this case, the only function the right side of the brain was serving was generating seizures.”

“Based on this knowledge and our own experience, we were confident this surgery was the best option,” adds Zafar.

The surgery required Vestal to make five major cuts to disconnect the epileptogenic portion of the brain:

- Corpus callosotomy to disconnect the “main superhighway” that unites the two hemispheres of the brain

- Frontal disconnection to separate the frontal lobe from the rest of the brain

- Occipital disconnection to sever the occipital and parietal lobes

- Temporal lobectomy or resection of a small portion of the temporal lobe

- Insular disconnection of the basal ganglia

The patient experienced minimal blood loss and remained in the hospital for two nights following surgery. Two weeks post-op, Vestal evaluated the patient for signs of infection and hydrocephalus, including headache, nausea and vomiting. One month after surgery, the patient had returned to baseline and was walking with the help of physical therapy to address slight weakness on her left side.

The patient was seizure-free immediately after surgery and has not had a seizure in nine months. Zafar has titrated her medications and expects to eliminate the last of three drugs at the one-year mark. “She’s doing amazing. Her development and learning has started to bloom,” he says.

As a Level 4 Epilepsy Center, Duke is recognized for providing the highest level of epilepsy care, including complex procedures like this one.

Both Zafar and Vestal understand that a surgical resolution for neurological conditions isn’t always an easy choice for parents, even if they’ve been caring for a child with challenging side effects like recurrent seizures. “Unless you have seen children on the other end of these high-risk, high-reward surgeries, it’s hard to make parents comfortable with this decision,” says Zafar. “We are confident in our team and our ability to do these procedures successfully. We pass this strength and confidence on to parents.”