Patient’s Faith Necessitates Alternative Treatment for Heart Failure

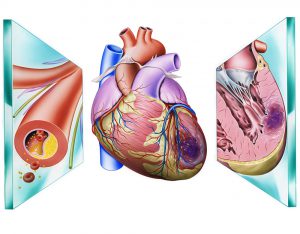

A 35-year-old man was referred to Duke in cardiogenic shock with heart failure. His cardiovascular health had declined for several years despite an aortic valve replacement previously performed at Duke.

Heavily vascularized tissue from the sternotomy during the aortic procedure increased the patient's risk of bleeding. His religious beliefs also presented challenges.

As a Jehovah's Witness, he refused blood transfusions, including autologous transfusions. Some Jehovah's Witnesses choose to accept minor blood fractions or undergo dialysis or cell salvage when kept in circuit with their own blood, but any surgical solution carries a risk of significant blood loss.

Question: What solution was recommended to accommodate the faith of the patient while offering a medically safe, long-term solution to the patient’s high-risk condition?

Answer: After stabilizing the patient, a multidisciplinary assessment team decided they could perform a heart transplant without transfusion.

Treatment began with implantation of an intra-aortic balloon pump, a consult from the Duke Center for Blood Conservation, and the development of a medical strategy to sustain and strengthen the patient’s circulatory function, says Chetan B. Patel, MD, an advanced heart failure specialist and medical director of the heart transplant program. “We considered every possibility, but it was obvious very quickly that medical therapy alone would not be sufficient,” he says.

The third “bloodless” transplant by Duke since 2015, the procedure underscores the medical center’s commitment to offering complex treatment options tailored to individuals with religious objections to certain medical therapies.

Nicole R. Guinn, MD, medical director of the Duke Center for Blood Conservation, recommended using epoetin alfa and intravenous iron to increase the patient’s red blood cell (RBC) count. These efforts proved effective in achieving a higher RBC count, improving the patient’s kidney function, and reducing the effects of pulmonary edema—3 goals deemed essential to making the patient eligible for transplantation.

Once these goals were achieved, the patient was placed on the transplant list. Within days, an organ became available.

“When the procedure began, we moved slower and more carefully than normal to dissect the heart from the remainder of the chest where adhesions had been created in the previous procedure,” says Mani A. Daneshmand, MD, a Duke heart surgeon. “This step presented a significant risk of bleeding.”

Wary of sudden blood loss, the surgical team, which included Daneshmand, Patel, and the surgical director of heart transplant, Carmelo A. Milano, MD, did not close the chest immediately following the procedure for 2 reasons: (1) the right ventricle can be crowded by the breast bone, which may increase the need for mechanical support, and (2) inserting the wires and screws required to close the chest introduces further risk of bleeding at a critical juncture in the procedure.

“We also spent extra time during the surgery to keep track of the RBCs and retrieve them,” recalls Daneshmand.

The patient recovered on a schedule typical following transplantation. “This was a case that required multiple specialists, including nurses, device experts, and a team of physicians in a highly collaborative partnership,” says Patel.