Using a nonmydriatic imaging device to screen patients for diabetic retinopathy (DR) in primary care clinics, Duke researchers found that a remote diagnosis model is as effective a tool as a traditional examination in identifying this sight-threatening disease, according to a study published in May 2019 in JAMA Ophthalmology.

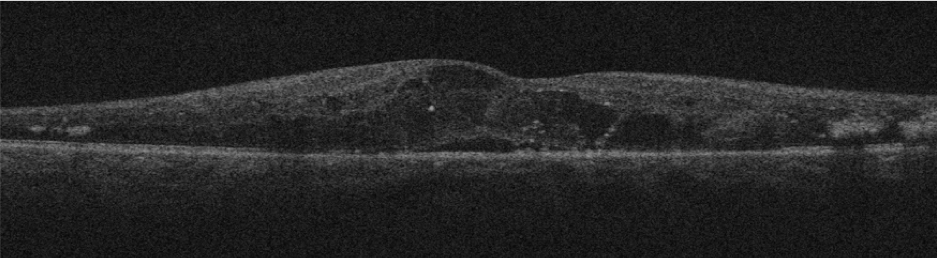

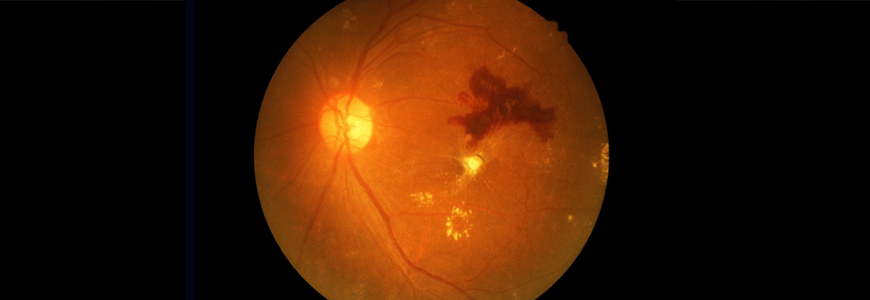

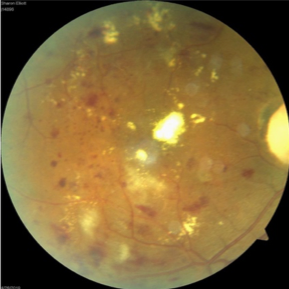

The nonrandomized study of 159 patients in Duke clinics that have relatively high retinal disease prevalence tested the feasibility of a remote diagnosis model for DR, which combined optical coherence tomography (OCT) and color fundus photography (CFP) imaging on patients’ undilated pupils to create a cross-section of the retina. The researchers also conducted field testing at a Duke primary care clinic in which participants underwent both a remote eye screening and a specialist examination with ancillary testing at the Duke Eye Center.

“Combining the two methodologies significantly improved the screening outcomes and provided much better interpretability with the cross-section images,” says Majda Hadziahmetovic, MD, a retinal specialist and lead author of the study. “With CFP imaging only, there is a high percentage of uninterpretable images, but with OCT, we had only one uninterpretable image out of all the patients we saw.”

Hadziahmetovic says that CFP alone is only interpretable in about 70% of cases. “In the images we can’t see well, it’s because people may have small pupils, cataracts, or other issues. The addition of OCT provides the image even when these kinds of obstacles exist,” she says.

DR is the No. 1 reason for vision loss in the working population in the U.S., Hadziahmetovic says. This remote diagnosis model for screening and triaging patients aims to facilitate efficient high-volume screenings of retinal diseases and improve the quality-of-care metrics for annual screening of patients with diabetes, potentially decreasing the number of physician appointments they need to make. “Those with diabetes tend to have a lot of comorbidities, including kidney function and high blood pressure, so they need to prioritize which appointments they need to go to, especially for those who are still working,” she adds.

While not every patient with diabetes has pathology, it is estimated that 35% do have pathology at the back of the eye. One participant in the primary care clinic field testing—a 49-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes who was not receiving any care prior to her remote diagnosis of nonproliferative DR—saw significant improvement in the retina appearance after her first injection treatment at Duke Eye Center.

“Even with the relatively small number of patients who were screened, we caught a substantial amount who need retinal care, ” Hadziahmetovic says.

The American Diabetes Association guidelines stipulate that patients with type 1 diabetes should be screened within five years of a diagnosis while those with type 2 diabetes should receive a dilated retinal examination at diagnosis. This remote diagnosis imaging model could help to better triage the 2 million people in the U.S. who have DR, especially for elderly or immobile patients or those who live in rural areas with a shortage of ophthalmic experts.

“As of now, there is no triaging being done in terms of who sees the patient for the exam at the primary care level,” Hadziahmetovic says. “With the remote imaging device in a primary care provider’s office, the physician would receive automated image interpretation and can tell a patient whether they have the pathology and discuss which type of health care provider would be best for them.”

As next steps, Hadziahmetovic says her team plans to test the remote diagnosis model in settings with relatively low disease prevalence—"everywhere people need screenings but may not have access to them,” she says. “We want to be on the forefront with this new way of diagnosing these patients in the United States and set an example of how this should be done.”