New Material to Repair a Common Joint Injury

A 54-year-old man active in calf roping and other rodeo events underwent surgery for a severe rotator cuff injury. That repair eventually ruptured; a second repair was attempted, but his shoulder still didn’t heal.

He came to Grant Garrigues, MD, an orthopaedic surgeon and specialist in shoulder surgery at Duke, to learn whether anything further could be done. The patient presented with pain, weakness, and loss of motion, so he wanted to learn more about shoulder replacement surgery.

Although anatomic total shoulder replacement provides excellent range of motion to patients with arthritis, it is not an appropriate option for those with rotator cuff tears. A second option—reverse ball-and-socket replacement—is specifically designed for patients with large rotator cuff tears, but the patient’s activity in high-impact sports made this a poor choice for him.

In consideration of a third repair, Garrigues conducted a thorough examination of the tendon, the results of which revealed that the tendon was greatly retracted with tissue loss from the patient's injury and his 2 previous surgeries. Some of the rotator cuff muscle had degenerated into marbled, fatty tissue. However, much of the muscle remained, so lengthening the tendon to its original attachment with a repair strong enough to heal was going to be challenging.

Garrigues decided to perform arthroscopy, a type of minimally invasive surgery, carefully dissecting the scar tissue that encased the tendon. For additional strength, he augmented the repair by placing a sterilized, natural material across the attachment area held in place by a field of strong sutures.

Question: What material was deemed strong and effective enough to provide a foundation for healing this difficult tear?

Answer: Garrigues used sterilized pigskin because its toughness and flexibility added strength to the repair. “The pigskin also serves as a scaffold for the body’s own stem cells to incorporate and to promote healing,” Garrigues says.

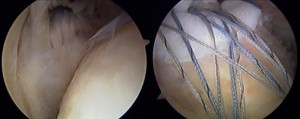

Figure 1. Intraoperative arthroscopic images showing the bald head prior to repair (left) and the rotator cuff with graft and sutures after repair (right)

The arthroscopic-assisted xenograft patch was completed and held in place with a strong field of sutures, and imaging confirmed that the rotator cuff tendon had begun to heal (Figure 1).

The patient recovered his shoulder strength, range of motion, and—most importantly—returned to "ropin’ and ridin’" pain free.

In addition to using pigskin for challenging repairs, Duke is adopting several new shoulder techniques and repair technologies. Duke is also participating in a worldwide trial of 15 orthopaedic centers to evaluate use of a smoother material coating for the ball in shoulder replacements that may benefit young, active patients with arthritis of the shoulder.

Duke specialists are also investigating a new, minimally invasive surgical technique for the treatment of irreparable rotator cuff tears that don't require joint replacement. The technique has been successfully used to rebalance the shoulder without any metal parts, thus giving patients improved strength and range of motion.