Mysterious Onset of Recurrent Seizures

An otherwise healthy, 27-year-old man consulted his primary care physician after waking up with body aches, head and neck stiffness, and fever. He reported seeing a tick-like insect in his bed, so his blood was submitted for Lyme disease testing. Because his symptoms were also concerning for meningitis, he was immediately started on empiric therapy with doxycycline.

All test results came back negative, but the patient continued to have a fever and became increasingly fatigued. Then one night, just 6 days after his symptoms first presented, the patient’s wife found him unresponsive. She rushed him to the local hospital where he experienced a generalized tonic-clonic seizure and was transferred to a larger center.

At the center, he was started on an antiepileptic medication but continued to have seizures with difficulty breathing. He was intubated and placed on a ventilator and transferred to Duke.

Question: What approach was necessary to save the patient’s life?

Answer: Multiple conditions can cause refractory seizures, so it was important that, in addition to treating the seizures, the team identify the underlying cause. In this case, antimicrosomal antibodies were detected, and the patient was diagnosed with autoimmune encephalitis.

Although limbic encephalitis was first described in the 1960s, autoimmune encephalitis as a distinct entity caused by autoantibodies targeting neuronal cell surface antigenic epitopes wasn’t discovered until relatively recently, explains critical care specialist Christa Swisher, MD, who helped treat the patient. “Before then, we would try to treat the patient’s seizures, but we couldn’t get to the underlying cause.”

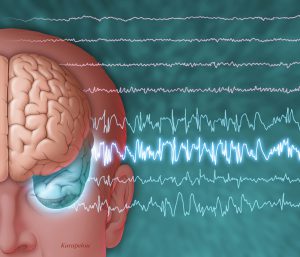

When the patient first arrived at Duke, the medical intensive care unit team placed him on continuous electroencephalography (EEG) monitoring. Unsure of the cause of the seizures, they then sent his blood and cerebrospinal fluid to the laboratory for extensive testing and performed ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging.

In the meantime, a neurocritical care team started him on several antiepileptic medications as well as propofol. When his seizures continued, they increased the dose of propofol to medically induce a coma to prevent further brain damage. Pentobarbital and midazolam were added soon after.

The patient had developed super refractory status epilepticus and was at risk of significant kidney, liver, and cardiovascular problems, among others, from the various, highly toxic, antiepileptic medications. The team was running out of options.

“At this point, a lot of places might have thrown in the towel,” says Christa Swisher, MD, who was part of the neurocritical care team who treated the patient. “But we weren’t ready to give up. We knew we still had some things we could try.”

It was then that the team learned that the patient’s blood was positive for antimicrosomal antibodies. The neurocritical care team administered plasmapheresis and intravenous immunoglobulin to attempt to remove autoantibodies and prevent them from causing irreversible brain damage.

The patient’s seizures did not stop immediately, so he began chemotherapy to further suppress his immune system. The neurocritical care team also successfully applied for expanded access (compassionate use) of allopregnanolone, a neurosteroid medication that is being studied for the treatment of super refractory status epilepticus.

Finally, 6 weeks after they had started, the patient’s seizures stopped. He began to come out of the coma and regain neurologic function.

“Although we can speculate that it was the allopregnanolone, it’s impossible to pinpoint what turned him around, since, without the luxury of time, we had to layer on multiple medications at once,” notes Swisher. “The important point is that we had the expertise to feel comfortable using the most recently approved medications and to apply for compassionate use of a new medication.”

Since coming out of a coma, the patient’s recovery has been slow and not without its setbacks—he will likely be on some antiepileptic medications for the rest of his life. Still, he has been able to return home, and, recently, he and his wife welcomed their first child into the world.

“The fact that he survived this is nothing short of a miracle,” Swisher concludes.