After years of seeking treatment for painful intercourse and menstrual leakage issues, a woman in her mid-20s was diagnosed with a longitudinal vaginal septum, a rare congenital anomaly that causes the vagina to be separated into two cavities due to the presence of an extra wall of tissue. This second cavity is not easily detected during typical gynecologic exams, particularly because one side of the vagina becomes dominant after the start of sexual activity; inserting a speculum in this side obscures the view of the non-dominant vaginal cavity.

Relieved to finally receive a diagnosis, the woman asked how this condition would affect her plans to become pregnant and have a vaginal delivery. The regional provider was not familiar with managing this type of condition but advised that while the vaginal septum would allow for vaginal delivery, it would tear and potentially require revision surgery. From a sexual health perspective, this woman was also interested in addressing her pain with intercourse, which had been a barrier in trying to conceive.

Dissatisfied with this answer, the woman sought a second opinion at Duke and self-referred to Cassandra K. Kisby, MD, MS, an obstetrician/gynecologist, urogynecologist, and fellowship-trained expert in female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery. With her advanced experience in treating Müllerian anomalies, Kisby was confident that she could create a better outcome and quality of life for the patient.

Question: How did Kisby approach this patient’s case to resolve her symptoms and address her concerns about pregnancy complications?

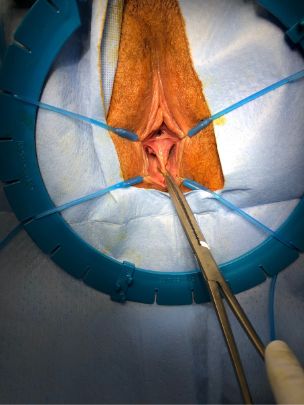

Answer: After talking at length with the patient to help educate her about the condition and to better understand her health goals, Kisby ordered an MRI to rule out any kidney issues, which are often present with congenital genitourinary anomalies. Kisby then performed a thorough exam on the patient under anesthesia and surgically removed the septum.

“The key in removing a vaginal septum is that you don’t take too much,” Kisby says. “There’s a Goldilocks zone: You want to take just enough to create one lumen that will be more functional for the patient, but you don’t want to take so much tissue that you are then struggling to reapproximate the edges of the vagina and narrow it such that the patient continues to have pain during intercourse.”

The procedure itself takes 30 to 45 minutes, and patients are discharged the same day, usually with minimal pain. Most patients are back to functional activities of daily living within a week, but post-surgical care must include vaginal dilation so that fibrotic scar tissue does not form. The patient is also restricted from intercourse and tampon use for six weeks to allow for proper healing.

Although not all vaginal septum cases require treatment, this patient’s goals necessitated this approach, Kisby explains. Surgically modifying the septum helps decrease the pain, improves menstrual management by enabling patients to wear tampons instead of pads, and allows for vaginal delivery without fear of breaking through the existing anatomy.

“The biggest thing I do at the beginning of my visit is to tell patients that they’re not alone, and that even though their condition is coded as an anomaly, they themselves are not an anomaly—it’s just an anatomic difference,” says Kisby, adding that the incidence of these congenital anomalies may be more common than some literature might cite.

Helping women with Müllerian anomalies navigate care

Providers with Duke’s Müllerian Anomalies Program help women to navigate the questions around their condition and determine what their best options are. By collaborating closely with urologists, colorectal surgeons, and pediatric and adolescent gynecologists, Kisby and colleagues investigate how to safely and effectively offer innovative therapies to appropriate patients. Jennifer O. Howell, MD, a pediatric and adolescent gynecologist, and Alison C. Weidner, MD, a urogynecologist, round out this comprehensive team of congenital genitourinary anomaly specialists.

“Often, in these cases, patients don’t expeditiously get answers for why they have pain until they come to a provider who has extensive experience with diagnosing and treating it,” Kisby adds. “It’s important for providers to know to look for issues with the kidney, bladder, and urethra, which can form congenitally along with the Müllerian anomaly.”

The related conditions that Duke experts treat include:

- Vaginal anomalies: Vaginal agenesis (absence), vaginal septum (longitudinal, transverse, or oblique)

- Uterine abnormalities: uterus didelphys (double uterus), arcuate uterus (curved), unicornuate uterus (one-sided), bicornuate uterus (heart-shaped), septate uterus (partitioned), absent uterus

- Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser (MRKH) Syndrome, an undeveloped uterus and upper vagina with external genitalia that appear normal

- Obstructed hemivagina and ipsilateral renal anomaly (OHVIRA), which includes uterus didelphys, unilateral low vaginal obstruction, and same-sided absence of a kidney.