Locating the Site of Obscure Bleeding

An 81-year-old woman presented to her local hospital with melena, chest pain, and fatigue. An initial upper endoscopy and colonoscopy failed to reveal the source of bleeding, but her hemoglobin continued to drop, and she required repeated blood transfusions.

During the ensuing 6 weeks, she was repeatedly admitted to the hospital and underwent multiple additional tests. Repeat upper endoscopy showed what appeared to be a small arteriovenous malformation, but she continued to bleed, even after it was treated. A tagged red blood cell scan revealed active bleeding, prompting 2 angiographies with coil embolization. Still, the bleeding persisted.

Finally, video capsule endoscopy showed active bleeding in her mid to distal small bowel. She was transferred to Duke for further management.

Question: How was the source of the bleeding identified and accessed?

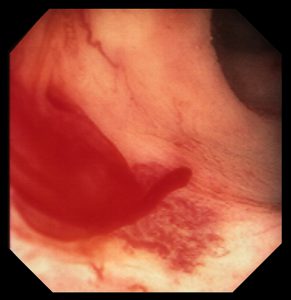

Answer: Spiral enteroscopy was used to reach the source of the bleeding: a Dieulafoy lesion in her distal jejunum.

At initial presentation, it was unclear whether the bleeding was caused by previous interventions—sometimes procedures like angiogram-guided embolization can lead to ischemia and related problems—or a lesion that had not been found on her previous interventions, explains Daniel M. Wild, MD, the gastroenterologist at Duke who treated the patient. Spiral enteroscopy allowed Wild to explore a large portion of her small bowel and to identify the source of the bleeding, a small raised area of brisk, active mucosal bleeding, consistent with a Dieulafoy lesion.

“Dieulafoy lesions can be very hard to see using angiography and other common diagnostic tools unless there is active bleeding at the time of the procedure,” he notes. “And this was a fairly challenging case since the segment with the bleeding was so far down in her small intestine.”

Once he had located the site of the bleeding, Wild placed 3 endoclips and marked the area with a tattoo. The patient’s bleeding stopped, but a week later, her red blood cell counts had once again dropped.

Wild repeated spiral enteroscopy and was again able to identify the site of active bleeding, as confirmed by the presence of the previously placed tattoo. The 3 clips from the initial procedure had been dislodged. He placed 7 new clips, and the bleeding stopped. Now, several months later, the patient has had no evidence of recurrent bleeding.

“Unfortunately, we don’t always find as definitive a source for obscure bleeding as we did in this case,” Wild says. “This patient was a relatively healthy but frail older woman who had been in and out of the hospital for 6 weeks before being transferred to Duke where we were able to identify the clear source of her bleeding and fix it. She’s had no further bleeding.”