As an active service member, a woman in her early thirties was required to undergo regular health screenings. One of these routine check-ups revealed unilateral proptosis affecting the right eye. Despite the subtle impact on her vision, the woman dismissed the condition initially. However, when the bulging eye became a cosmetic impediment, she sought further evaluation.

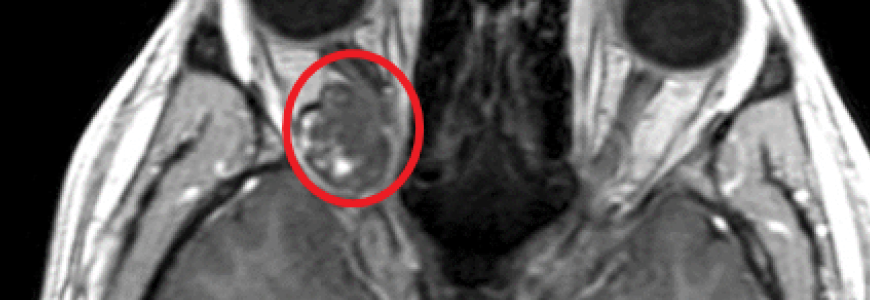

“She presented to us with progressive neurological deficits, specifically proptosis and double vision, so we obtained an MRI and confirmed that she had a retrobulbar intraconal cavernoma localized to the apex of the orbit,” says microvascular surgeon/neurosurgeon David M. Hasan, MD, MSc.

The slow-growing cavernoma had reached a size of 15mm. According to Hasan, the large size of the cavernoma and its location made this case unique. “Usually, these cavernomas are small and floating in the periorbital fat, so it’s easy to extract them,” he says. “This one, we discovered, was adherent to the ocular muscles, optic nerve, and other extra-ocular nerves so removal was very difficult. There was a high risk of compromising her vision and/or causing permanent double vision.”

Question: How did the Duke surgical team remove the cavernoma without serious injury to the eye?

Answer: Hasan and oculoplastic surgeon Jason Liss determined that the mass was too large and too precariously positioned to remove the cavernoma using a minimally invasive transconjunctival approach. After consulting with the patient, the team opted to perform a craniotomy, approaching the cavernoma from the lateral part of the orbit.

“We were able resect it completely,” says Hasan. “It was a very difficult and delicate procedure because we had to respect all of the tiny, wispy nerves, the muscle and the tiny arteries in the eye. Any injury to those structures and patient would be blind.”

The patient remained in the hospital for four days after the surgery. Her follow-up care included an MRI to confirm total resection and an oculoplastic evaluation to monitor swelling. “Three months after the surgery, she had improved completely and was back to baseline,” says Hasan.

As the only CCM Center of Excellence in North Carolina and the Southeast region — and one of just a handful of designated centers across the country — Duke is recognized for performing a high volume of complex procedures like this one to successfully treat cerebral cavernous malformations. The designation is a testament to the comprehensive and multidisciplinary care Duke offers. And it’s a nod to its long history of innovating in this field.

“Our own researcher, Doug Marchuk, discovered the genes responsible for the hereditary form of CCM,” says Hasan. “This designation highlights our ongoing commitment to discovering new ways to diagnose the disease and provide effective care.”