Informed Imaging Improves Safety for Children

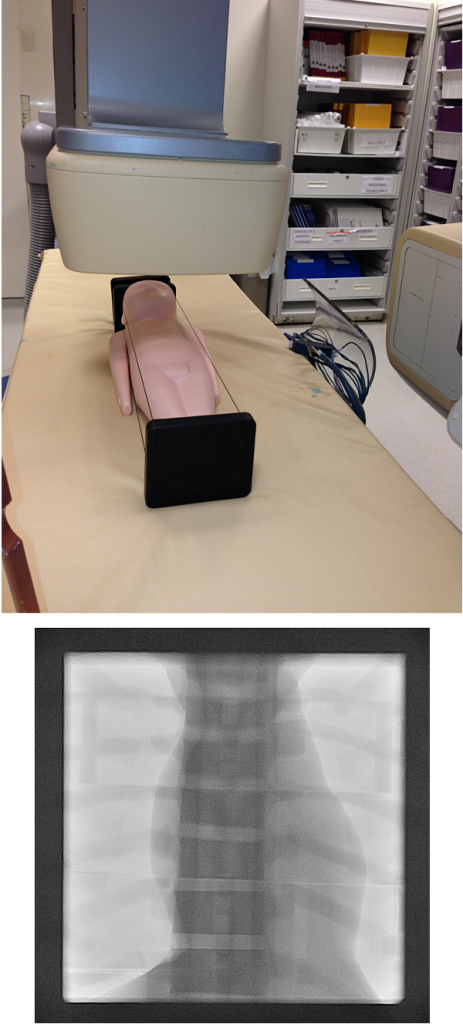

FIGURES 1 and 2: (1) A neonatal phantom is used to test the imaging equipment in Duke’s pediatric catheterization laboratory. (2) A chest X-ray from the phantom looks just like an X-ray from a baby because the phantom tissues are specially designed to absorb radiation in the same way. By using the phantom, Duke physicians can test different approaches to ensure that their procedures are as safe as possible.

Children with complex diseases, such as congenital and acquired heart disease, frequently have complicated medical needs, sometimes requiring multiple surgeries and experiencing long hospitalizations. As a result, they are often exposed to many procedures involving ionizing radiation. Although the procedures are important for making an accurate diagnosis and planning the most effective course of treatment, ionizing radiation itself is potentially harmful and can lead to an increased risk of cancer over a patient’s lifetime.

Striking the right balance between performing the procedures necessary to care for patients while minimizing the risk of potential harm is a focus of the Duke Departments of Pediatrics and Radiology, together offering all imaging modalities for evaluating all organ systems in children.

Kevin Hill, MD, a pediatric cardiologist, and Donald Frush, MD, a pediatric radiologist, are specialists at Duke in the field of medical radiation safety for children, leading research studies, developing recommendations, and educating clinicians internationally. Hill and Frush note that there are 2 central tenets of radiation safety in medicine: optimization and justification.

“Optimization means that we do everything we can to minimize the radiation dose for any given procedure, while at the same time making sure we don’t compromise the quality of the study,” says Hill. “One of the unique strategies that we use at Duke to ensure that these procedures are as safe as possible involves using phantoms that represent children of different ages. We are constantly testing our imaging equipment and trying out different methods for lowering radiation doses. With the test results, we can implement changes to our protocols where possible” (see Figures 1 and 2).

For justification, clinicians are advised to “take a step back” to ensure that a procedure is performed for the right reasons and that it’s the best possible procedure for evaluating the patient’s condition. “Sometimes, radiation-free modalities can be just as effective, so we try to personalize procedures to the needs of each patient,” says Hill. By following these principles, the diagnostic quality of procedures is not compromised, and the lowest acceptable radiation dose is used.

On a national level, Frush and Hill are active in the Image Gently Alliance, a coalition of health care organizations founded in 2007 to answer a call from patients, the public, industry, the scientific community, government agencies, and radiologists to improve the safety and quality of pediatric imaging. The Alliance seeks to ensure that facts and recommendations involving radiation safety are communicated to a broad audience worldwide, including patients, caregivers, the general public, providers, and imaging professionals, especially radiologists.

Frush is one of the founding members of the organization and currently serves as its Chair; Hill led the organization’s Have-A-Heart campaign, designed to spread the word about radiation safety for children with heart disease through publications, presentations, media releases, and educational opportunities.

As part of their work with Image Gently, Frush and Hill co-authored a consensus guideline paper, available as an open-source publication, in JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging. Published in July 2017, recommendations were focused on the management of patient dose while maintaining diagnostic quality images and included guidelines for hardware and software configuration and operator-dependent techniques.

“This was the first paper that was endorsed by multiple medical specialty organizations and that presented a comprehensive review of potential radiation risks as well as dose-reduction strategies in children,” says Frush, who also serves with the National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements and committees of international agencies including the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and the World Health Organization.

“Anything we can do to reduce radiation exposure in children to the lowest possible degree without compromising the study quality is important,” says Hill. “Our message is simple: ‘Don’t compromise care by not doing the procedures, but if you’re going to do them, do them safely.’”