Growing Patient Demand Spurs a Specialized Clinic

Beginning with a broad focus on lupus and autoimmune-related disorders, a rheumatology faculty member at Duke Health gradually shifted her emphasis to inflammatory myopathies to accommodate growing patient demand for the treatment of these classically painless muscle weakness disorders.

Specializing in myositis has driven growth at the clinic because of informed, proactive patients who share disease-management ideas and communicate through online forums to promote favored health care professionals. Clinic director Lisa Criscione-Schreiber, MD, says patients come from across the southeastern United States.

Criscione-Schreiber has focused on myositis for several years. In 2014, she began collaboratively working with Elizabeth Baran, MSN, a nurse practitioner, to develop her skills in the diagnosis and management of myositis to create a practice that could accommodate more patients.

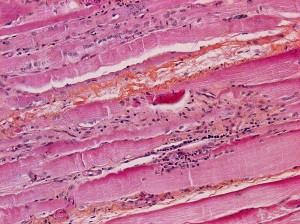

Inflammatory myopathies cause pain in some patients, she notes, but most diagnoses are based on objective muscle abnormalities, including findings on electromyography, magnetic resonance imaging, or muscle biopsy. The presence of certain skin rashes may also be a marker.

Criscione-Schreiber collaborates with dermatology colleagues to manage skin manifestations of myositis. Duke physicians at the Muscular Dystrophy Clinic also help differentiate inflammatory disorders.

Often mistakenly diagnosed as lupus or another autoimmune-related disorder, myositis is sometimes suboptimally treated. “It’s a hard group of diseases to diagnose and treat effectively,” she says.

Elevated levels of creatine kinase may also indicate myositis and are commonly found in the work-up. “But, the myositis diseases are highly variable with some rare forms and many different prognoses,” she says.

Criscione-Schreiber explains that she vigilantly screens newly diagnosed patients for cancers during the first 2 years because of a clinical link between cancer development and myositis. Another risk from myositis is inflammatory lung disease, which can be fatal.

“Myositis gets bad quickly,” she says. “Unfortunately, it gets better very slowly.”

She encourages regional rheumatology clinics to refer complex cases as soon as possible if patients do not improve after early treatment. Because of the challenging diagnosis process, a patient’s long-term health may be at risk.

Using a combination of high-dose immunosuppressant therapies is a common initial treatment, but Criscione-Schreiber says a consistent challenge is determining when the disease is active after treatment. By monitoring patients over several years, she says her specialized clinic is able to more effectively plan treatment modalities.

Criscione-Schreiber, who also directs the Duke Rheumatology Fellowship Training Program for 3 fellows each year, adds that new research being conducted is also helping physicians treat inflammatory myopathy.