When a patient presents with inflammation, pain, or swelling in a salivary gland, particularly when symptoms are exacerbated by eating, initial management may include warm compresses, massage of the gland and sialagogues. But these limited conservative approaches may still result in an inadequate response in up to 40% of patients and may not resolve the underlying issue.

That’s when sialendoscopy — a minimally invasive, gland-sparing procedure newly available at Duke — may come into play. Liana Puscas, MD, MHS, a Duke otolaryngologist and head and neck surgeon, highlights the diagnostic capabilities and interventional modalities of this approach.

How sialendoscopy works

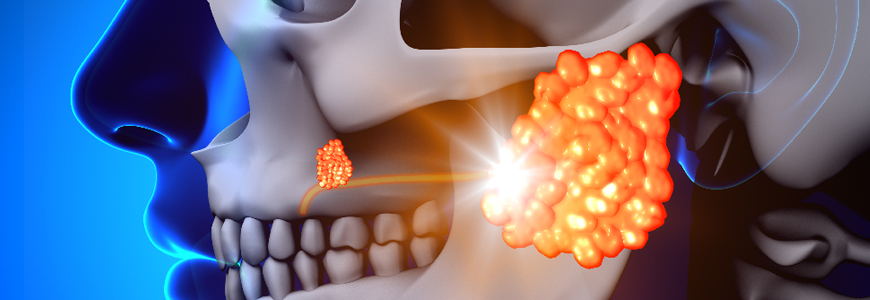

Sialendoscopy is used to examine the ducts of the salivary glands (typically the parotid or submandibular gland). A micro-endoscope is inserted into the natural opening of the salivary gland duct as it enters the oral cavity, allowing for visualization of the ductal lumen.

Patients most appropriate for sialendoscopy are those with confirmed distally located sialolithiasis or chronic salivary gland infection due to inflammatory disease, trauma, or an idiopathic stricture, Puscas says. Sialolithiasis most commonly affects people ages 30 to 60, with men being more likely to develop the condition than women.

Though it is now standard-of-care at Duke, sialendoscopy is not a common service offered nationwide due to the cost of the ultrathin fiberoptic endoscopes, which are less than 2 mm in diameter. The structural integrity of the fragile equipment is easily compromised, and a facility must have multiple scopes on hand for patient care, she adds.

“This is an emerging skill, and not many people around the country have it,” notes Puscas, who is one of three Duke otolaryngologists to perform the procedure.

Diagnostic and therapeutic benefits of sialendoscopy

This technology is especially useful in cases when imaging cannot confirm sialolithiasis due to the nature of the stone, she says. Endoscopy can be diagnostic because it can find areas of stricture or unimaged stones, but it can also be therapeutic at the same time because you can dilate those strictures or use catheters to grasp and remove the salivary stone or administer directed medication, she adds.

This outpatient procedure does often require a small incision to extract the stone from the salivary duct, but once the duct opening is sewn to the tissue to ensure it stays patent, the saliva can flow easily again. Puscas notes that if a patient should ever develop another collection of grit in their salivary glands, the larger opening makes it easier for that fluid to escape, potentially preventing another stone from forming.

One major benefit to patients who undergo sialendoscopy is that it can save the need for an external incision and removal of a salivary gland if the stone can be removed intraorally or the duct can be dilated. “That's especially important for the parotid gland because the removal of the parotid gland requires putting the facial nerve at risk,” Puscas notes.

Cases not suited for sialendoscopy

Despite the technical advances in salivary stone removal, Puscas cautions that sialendoscopy is not curative for everyone. “If a patient has a large stone right at the hilum, where the duct comes out of the gland, you may not be able to avoid some type of external incision,” she says. “You may not have to do a total gland removal, but you're going to have to do some kind of external approach to get that stone out.”

In the submandibular gland, Puscas explains that the position of the stone matters: “It's whether or not the stone is above or below the mylohyoid muscle. If the stone is inferior to the mylohyoid muscle, then you can't extract it using sialendoscopy.” For the parotid gland, she explains that how and where the stone is located relative to the masseter muscle would determine whether sialendoscopy is possible.