The Duke Heart Transplant Program performed the nation’s first adult heart transplant using the donation after circulatory death (DCD) protocol in December 2019. That accomplishment and subsequent successful procedures highlight the potential of a recently concluded trial that demonstrated the potential to increase available hearts up to 30% nationally.

As one of five participating centers, transplant specialists say that Duke is leading the effort to address a longstanding shortage of donor hearts.

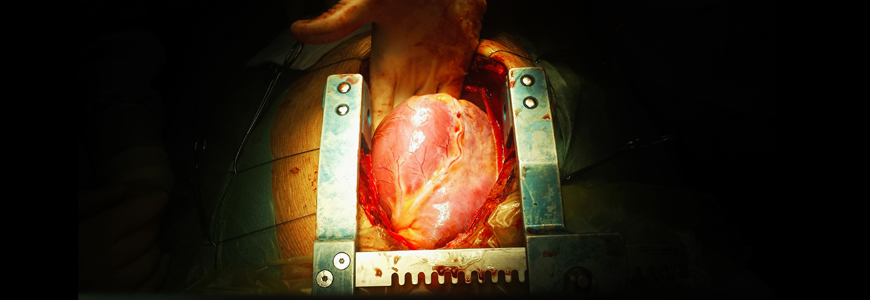

The Donors After Circulatory Death Heart Trial evaluates a portable system (TransMedics Organ Care System, TransMedics, Andover, MA) that transports the donated heart in a warm, perfused state with the donor’s blood in a medium that contains steroids, antibiotics, adenosine, vitamins, and other medications.

This system sustains the “living” organ from removal to implantation, allowing more time for transit and surgical preparation. Before the trial, donor hearts were transported on ice in coolers—a system with travel and geographical restrictions.

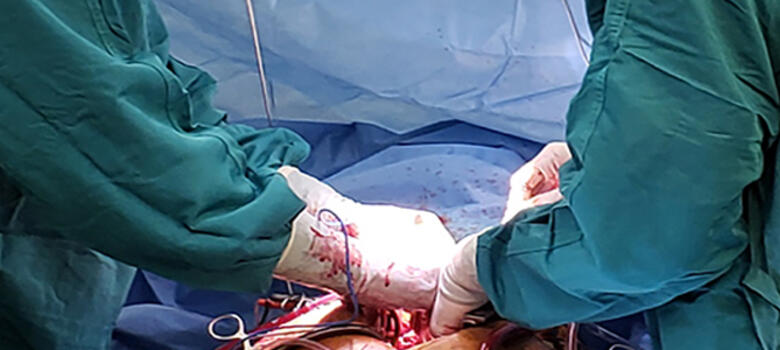

When the trial concluded in September, 35 hearts had been transplanted by the Duke team using the DCD protocol. (Of that total, 34 procedures were performed as part of the trial; one transplant took place under a compassionate use exemption).

During the trial, hearts were resuscitated and preserved after circulatory death instead of brain death. Within the DCD trial transplantation guidelines, death is declared once the heart stops beating, a process that has been performed routinely in the United States for organs other than the heart. Although the trial has ended, a special protocol will allow the Duke team to continue DCD transplants.

DCD organ preservation may expand donor pool by 30%

Cardiothoracic surgeon Jacob N. Schroder, MD, surgical director of the Duke Heart Transplant Program, says the DCD trial will help close the gap between the demand for donor hearts and the number of patients on waiting lists. The goal of the trial is to determine whether DCD transplant is equivalent to standard-of-care procedures when measured by survival and post-transplant rates of heart dysfunction.

“This procedure has the potential to expand the donor pool by up to 30% or about 750-1000 additional transplants each year, according to our analysis here at Duke,” says Schroder, who performed the first DCD transplant in December. “We also believe that increasing the number of donated organs is the first step in addressing the national shortage of donor hearts.”

Chetan B. Patel, MD, medical director of the Duke Heart Transplant Program, says the trial success sets the stage for leveraging perfusion technology to modify hearts to make the organs more resilient to rejection limitations. “We already working on that aspect at Duke,” he says. “When this work is coupled with broader regional organ sharing, this advance will ensure appropriate allocation of organs to those heart failure patients in greatest need.”

Approximately 3,400 patients were on the waiting list for a heart transplant in July 2020, according to the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN). In 2019, surgeons transplanted 3,552 hearts in the U.S.

But the increasing incidence of heart failure (HF) nationally signals an enormous challenge in future demand for donor hearts: 250,000 U.S. patients live with Class IV HF, the most severe category. Many need a transplant.

If only 10% of the patients with Class IV HF qualify for transplant, Schroder notes, demand for donor hearts would be at least 25,000. “Routine use of DCD hearts would be a significant, positive step to help meet this demand,” Schroder says.

“The major barrier to doing more transplants is a lack of suitable DBD heart donors,” he adds. “Significantly, of all of the hearts offered for donation, only 25% to 30% are actually used for transplantation.”