Diagnosing Prostate Cancer

For several years, a 68-year-old man was monitored for borderline high levels of prostate-specific antigen (PSA). When his PSA level increased to 6.7 ng/mL, he underwent biopsy of the prostate, but no tumor was detected. Seeking a second opinion, he consulted Thomas Polascik, MD, a Duke urologist.

Question: How was the patient diagnosed, and how did Polascik proceed following the diagnosis?

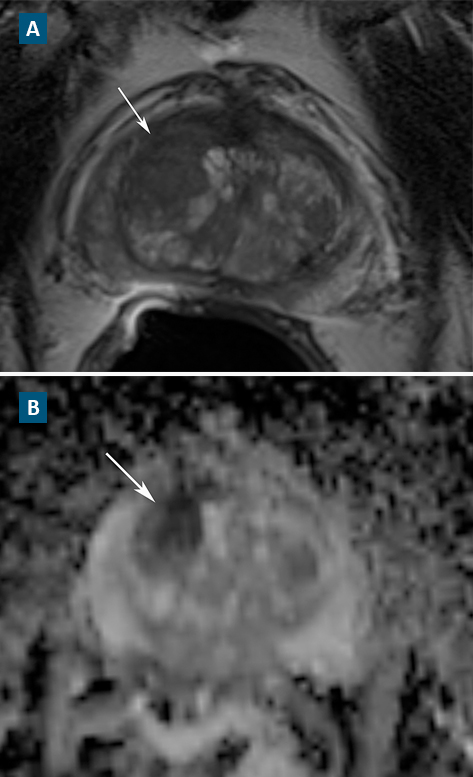

Answer: A 1.3-cm prostate lesion was found using multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging (MRI; Figure). Polascik employed MRI-transrectal ultrasonographic-guided (TRUS) fusion biopsy and anterior-gland focal therapy to ablate the tumor while sparing the surrounding nerve tissue.

FIGURE. (A) T2-weighted image and (B) apparent diffusion coefficient map

Whereas conventional biopsy can miss tumors—particularly those in the anterior portion of the prostate—multiparametric MRI is more effective at accurately characterizing clinically significant prostate cancer.

“Multiparametric MRI is changing how we look at patients with prostate cancer,” says Duke radiologist Rajan Gupta, MD. “High-quality imaging can give the urologist a map of the tumors and, more importantly, information on which ones are aggressive and which ones can be watched. It is helping to change the paradigm for prostate cancer treatment.”

Because significant experience and expertise are required to accurately perform and interpret findings on multiparametric MRI, Polascik works closely with Gupta to confirm the findings before proceeding with treatment.

In this case, multiparametric MRI revealed low-grade anterior prostate cancer, and Polascik discussed treatment options with the patient.

“We talked about surveillance, surgery, radiation, and hormones. He was otherwise quite healthy—he was continent, no sexual dysfunction, and no medical morbidities—so he didn’t feel comfortable with whole-gland radiation or surgery.” Instead, the patient opted to try anterior-gland focal cryotherapy, a targeted, nerve-sparing technique Polascik and his team recently helped develop.

Prior to surgery, a rectal swab culture was obtained to ensure it would be safe to use a fluoroquinolone, which is standard prebiopsy prophylaxis. Results of the culture revealed the patient would not require any special antibiotics.

“He was one of the fortunate ones without fluoroquinolone resistance, but he appreciated that we checked for him prior to biopsy,” says Polascik. “Rectal swab culture is not considered standard of care yet in the community, but I offer it to 100% of my patients—I have to keep them safe.”

After the rectal swab, Polascik performed multiparametric MRI-TRUS fusion biopsy, followed by anterior-gland focal cryotherapy a few weeks later. The patient’s urinary symptoms improved as a result, and he experienced no change in his potency.

One year after the surgery, multiparametric MRI was repeated, demonstrating that the cancer had been ablated and no new cancer had developed. In addition, Polascik performed biopsies of both the treated and untreated areas of the prostate, and no cancer was detected.

“We’re trying to balance the traditional mindset of conventional therapies with the recent push for surveillance,” Polascik observes. “Ultimately, we’ll have a better sense for how to treat only what’s necessary and when necessary—we aim to convert prostate cancer from an acute disease to a chronic, manageable condition like diabetes or hypertension.”