Pediatric patients undergoing cardiac surgery are at high risk for injury to the recurrent laryngeal nerve, which is susceptible to injury anywhere along its long, winding path to the larynx. A stun, stretch, or inadvertent cut during surgery can cause temporary or even permanent unilateral vocal fold paralysis. Specialists agree this condition is often underreported.

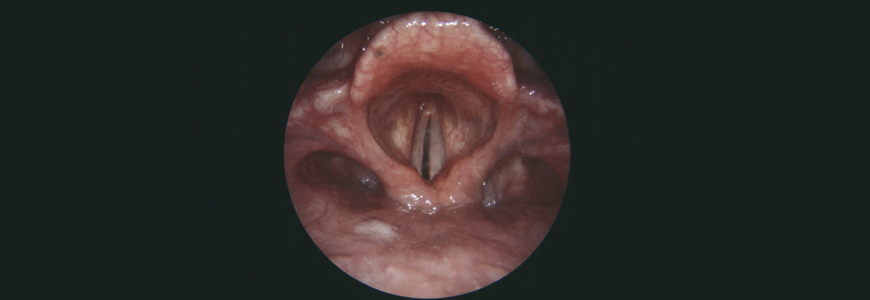

Part of the reason for the underreporting may be that symptoms range widely: patients may be initially asymptomatic or develop a voice change described in a variety of ways, including raspy, hoarse, breathy, or quiet. In order to make sound, the vocal cords must touch one another when a patient vocalizes. If the paralyzed vocal cord is too far away, the mobile cord may not be able to make good contact with it, resulting in a weak voice.

Janet Lee, MD, a Duke pediatric head and neck surgeon, explains that while spontaneous recovery is possible, the severity of the injury and its long-term impact on the voice are difficult to assess for up to a year following a patient’s last cardiac surgery, as early as between the ages 1 and 2. Importantly, this condition can affect a child’s speech development and could cause parents and providers to miss cues due to a weak cry that may lead to more significant issues in the long term, Lee says.

“Kids typically present around age 5, when they’re starting school. A child with dysphonia sounds normal to the family because that’s how they’ve always sounded, but the parents often mention that their child has trouble being heard in groups or is out of breath, or that people are always asking if their child is sick,” she adds.

Screenings and Solutions for Pediatric Voice Disorders

Lee explains that few providers routinely assess for iatrogenic dysphonia in children following aortic arch surgeries, such as repairs for interrupted aortic arch or coarctation, or even patent ductus arteriosus ligations. “I think it should be something that is screened for in any kid that has had a congenital heart disease surgery involving a PDA or aortic arch manipulation,” she says.

If voice issues persist a year after this type of surgery, specialists may perform a surgical airway evaluation, an endoscopy, and a laryngeal electromyography (EMG), if necessary, to measure the nerve signals to airway muscles and determine whether the vocal fold is likely to recover. If the EMG indicates that the nerve is unlikely to recover, and the voice issues are significant, “there are procedures we can do now at Duke that didn't exist 20 years ago to improve the voice,” Lee adds.

Non-selective Laryngeal Reinnervation Surgery

One such procedure is the non-selective laryngeal reinnervation, which restores neural connections to the larynx and gives tone to the vocal cord using the ansa cervicalis rather than performing surgery on the larynx itself.

Lee explains how the surgery reinnervates the paralyzed vocal cord from a new source: “We identify the recurrent laryngeal nerve, trace it as close up to the larynx as we can from the outside of the neck, and cut it,” Lee says. “Then, we find the nerve that innervates one of the minor neck muscles used to swallow and connect it to the stump of the recurrent laryngeal nerve. This provides new tone to the paralyzed vocal cord, allowing it to sit closer to the working cord, which allows the patient to have a stronger voice and better airway protection.”

At the time of the reinnervation, the patient also receives an injection medialization, which gives them instant improvement in their voice. However, because injection wears out after three to six months, the child’s voice often takes a dip but then starts to come back as the nerve input begins to grow the muscle again. The full reinnervation takes about 6 to 12 months.

Comparing Options to Treat Vocal Fold Paralysis in Children

While other options—such as vocal cord injection medialization and laryngeal framework surgeries—may be appropriate in adults to physically move the paralyzed vocal cord closer to the functioning vocal cord, these approaches are suboptimal for pediatric patients because they require frequent procedures or can be impacted by the child's growth, Lee says.

“Injection medialization wears out and requires general anesthesia each time the procedure is done in younger children. Thyroplasty is permanent and involves implanting a silastic block into the larynx, but people are wary of putting long-term implants like that into children because of the potential for extrusion, infection, or migration into their trachea as they grow,” she explains.

Lee says that the non-selective laryngeal reinnervation is a better solution because it offers several key benefits, including permanent nerve input, no use of foreign materials, no need for an intraoperative judgment call to assess the voice (as is done in laryngeal framework surgeries), and no risk of scarring to the vocal folds.

“What’s unique to the non-selective laryngeal reinnervation surgery is that it’s done though the neck, and you’re not changing the structure of the larynx at all,” Lee says. “This is important because if the child’s voice is not satisfactory after they are finished growing, there are still options available to them because everything inside the larynx itself is the same.”

To learn more or to refer a patient, visit https://www.dukehealth.org/pediatric-treatments/pediatric-voice-disorders.