Complex Cardiac Patient With ESLD

In November 2015, a 28-year-old woman with a 7-month history suggestive of liver disease was admitted to Duke Health for evaluation. The hepatology team diagnosed her with end-stage liver disease (ESLD).

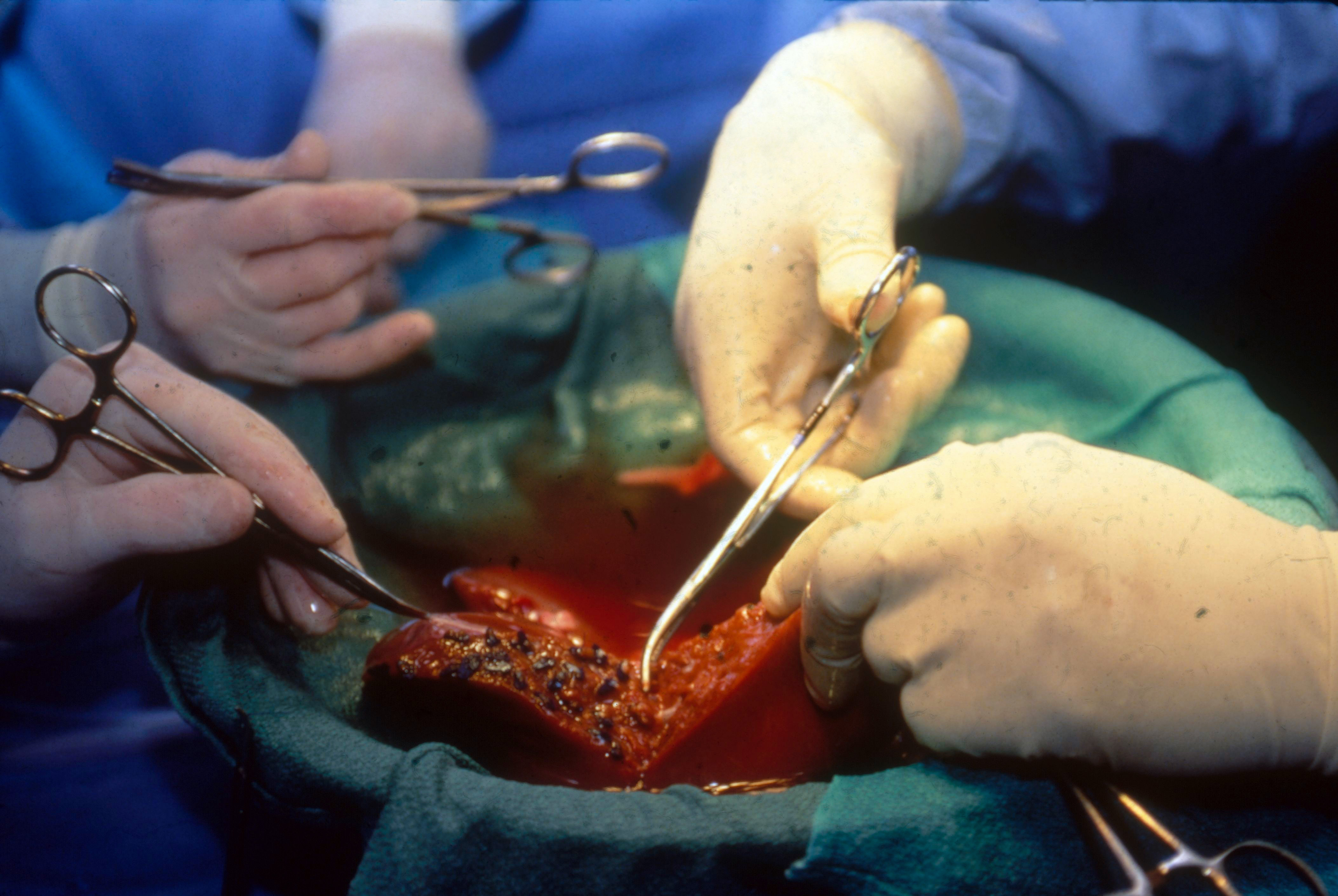

The best treatment option was a liver transplant. However, a transplant would be difficult because the patient had Brugada syndrome, a cardiac arrhythmia condition that can cause sudden death. An automatic implantable cardioverter-defibrillator was inserted when the patient was diagnosed at 21 years of age.

Liver transplantation usually requires the use of drugs to increase the ejection fraction of the heart, but these medications can also activate an automatic implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, triggering cardiac electrical storm. In a patient with Brugada syndrome, this could potentially lead to death.

Question: Was it possible for this patient to receive a liver transplant?

Liver transplantation places significant stress on the heart. Therefore, extensive assessment of cardiac function is routinely undertaken. Hepatologists, surgeons, anesthesiologists, transplant pharmacists, social workers, and nurse coordinators work in tandem to develop an individualized plan for each patient.

Arturo Suarez, MD, lead anesthesiologist, researched and recommended low-risk medications to manage the risks of Brugada syndrome on the patient's heart.

Transplant surgeon Kadiyala Ravindra, MD, collaborated with Albert Sun, MD, a consulting cardiologist and electrophysiologist, to assess the hemodynamic and arrhythmic risks to the patient.

“We have to identify techniques to overcome the difficulties that might occur. This often requires seeking the opinion of subspecialists and formulating a plan ahead of time,” Ravindra explains.

Sun adds that the dearth of literature on liver transplantation in the setting of Brugada syndrome prompted more intensive planning and coordination with Ravindra and Suarez.

“For this patient, we really worked together to set a clear plan to prevent any complications that the syndrome may cause,” says Sun.

Suarez tailored a medication regimen to prevent electrical storm during the transplant. “Different drugs are deployed at each stage of a normal liver transplantation,” he explains, “but we could not use many of them in this case because of the cardiac risks. We prepared an alternative progression of medications to protect her heart.”

When a donor liver became available, Suarez reviewed the final plan with the patient. “She burst into tears as she listened to the multiple challenges,” he says. “But, after our talk, she did a fist bump with us,” he remembers. “She was ready to fight.”

The patient received the liver transplant and was discharged from the hospital 13 days after surgery.

“Fortunately, the procedure went as per plan. She tolerated the anesthesia without incident. Her postoperative period was uneventful. The extensive discussions we had in the planning process were crucial in ensuring a good outcome,” Ravindra says.

“What this case really illustrates is that an unusual disease does not prevent someone from receiving a liver or kidney transplant,” adds Ravindra.

Using the same multidisciplinary approach for each case, Duke has been growing its liver transplantation program over the past 4 to 5 years, performing as many as 90 transplants every year.