Complex Adverse Effects Arise a Decade After Prostate Cancer Treatment

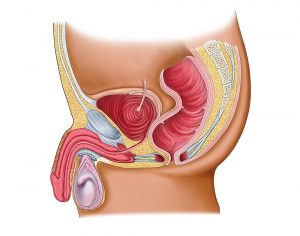

Ten years after receiving brachytherapy for prostate cancer in South Carolina, an active, 70-year-old ex-Marine developed severe complications, including rectourethral and vesico-symphyseal fistulas and osteomyelitis pubis. He received several temporizing procedures and was prescribed various antibiotics to treat the osteomyelitis, but, by the time he presented to Duke Urology, he was losing his ability to walk.

Question: What factors needed to be considered when approaching this patient’s treatment plan?

Answer: It was critical that the Duke team address the source of the problem—the fistula—rather than only focusing on the resultant infection. In addition, although the fistula was too large to be reconstructed, they needed to use a multidisciplinary approach that would maximize the patient's quality of life by letting him return to his active lifestyle.

Oncologists have been successful at developing treatments for prostate cancer that increase survival; now, more focus should be placed on treating the complications that can result from those treatments, says Andrew Peterson, MD, the Duke urologic surgeon who treated the patient.

“Even though a patient’s prostate cancer may be under control, that doesn’t mean we’re done with his care,” he stresses. “Some patients develop adverse effects from the life-saving care—sometimes 10 years after treatment—that can have effects on their quality of life.”

After Peterson and colorectal surgeon Christopher Mantyh, MD, examined the patient in same-day appointments, they consulted the detailed clinical care algorithm they had helped develop for the surgical management of complex rectourethral fistulas. The patient’s health was quickly deteriorating, so they scheduled him for extirpative surgery within the week.

The surgery lasted 12 hours and required the expertise of orthopaedic surgeon William Eward, MD, in addition to that of Peterson and Mantyh. First, Peterson and Eward removed the infected bone. For cases of severe bone infection, Eward explains, it is impossible to cure the infection with antibiotics alone; there isn’t enough blood flowing through to get the antibiotic to the site of infection. The infected bone must be removed.

“For many of these patients, this hasn't been recognized,” Eward notes. “Patients have been getting years and years of antibiotics, but without removing the infected bone, the infection will never be cured.”

Once the infected bone was successfully removed, Peterson took out the patient’s bladder and residual prostate before Mantyh removed his rectum and performed colostomy, attaching the ureter to a loop of bowel that exited through the patient’s skin. Finally, Peterson performed urostomy.

The patient had a smooth postoperative recovery and experienced no complications. He was discharged 7 days later.

“Unfortunately, because of how far the fistula had progressed by the time we saw him, the colostomy and urostomy will be permanent—he knew that ahead of time,” Mantyh says. “But it’s a whole lot better than where he was, dying a slow, painful death from the infection. He can now get back to enjoying his favorite activities like kayaking and hiking.”