Cataract Surgery in a Man With Phrenic Nerve Paralysis

When an active man from Georgia made the journey to the Duke Eye Center for dense cataracts in both eyes, he had already consulted 7 physicians in the southeastern United States. The patient's case was complex because he had bilateral phrenic nerve paralysis, a condition that made him severely dyspneic when he lies down horizontally.

Although the patient had a mask and bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP) machine he could use to help him breathe during surgery, the mask obstructed access to his eyes, and he was uncomfortable wearing it while lying on his back. He hoped to find a physician who could perform the surgery.

Question: How was the team at the Duke Eye Center able to perform cataract surgery?

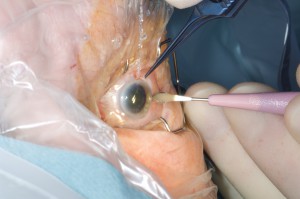

Ultrasonic phacoemulsification was performed and an advanced-design intraocular lens was placed because the positioning of the patient did not allow the surgeon to utilize femtosecond laser–assisted technology.

Alan N. Carlson, MD, the ophthalmologist who performed the surgery explains, “We weren’t really equipped to do the surgery in the position the patient could breathe in; the key was adapting our technology to his needs. Fortunately, we were able to find a position where the patient was almost sitting up but still reclining enough to allow us to use the microscope we need to perform the operation.”

Before the surgery, Carlson asked the patient to practice lying on his back while wearing his oxygen mask to minimize stress and help the operation go smoothly. He scheduled the surgery for a longer operation than the time usually required for cataract surgery to give his team time to set up to accommodate the tubing of the oxygen mask, the BiPAP machine, and the patient’s unique, semi-seated position. The operation itself took fewer than 6 minutes. There were no complications.

Carlson credits the patient’s positive outcome to the Duke Eye Center’s team approach. “All of our surgeries require good communication between the nurses, the anesthesiologists, the transport people, the patient, and ourselves,” he notes. “There’s a level of professionalism and respect across all areas—we are not silos. Meeting this patient’s visual needs was really all about our ability to work together with the patient to develop a plan that he could help us execute.”

The day after the surgery the patient’s vision had improved from a corrected visual acuity of 20/70 to an uncorrected acuity of 20/15. The patient was thrilled and immediately scheduled surgery on his other eye. Just 3 weeks later, he returned to his active lifestyle, writing and working as a leadership consultant.